Welcome to Climate Drift - the place where we dive into climate solutions and help you find your role in the race to net zero.

If you haven’t subscribed, join here:

Hey there! 👋

Skander here.

The energy world is at a crossroads: demand is skyrocketing with EVs, data centers, and electrification, while supply struggles against interconnection queues and transmission bottlenecks. And utilities are stuck in the middle, trying to deliver enough power to meet the demand.

Enter distributed energy resources (DERs) - a potential game-changer. But how do we harness their full potential?

In this 2 part guide, we're diving deep into the world of DERs and how they're reshaping our approach to energy production, consumption, and management.

Part 1 covers the essentials: the rise of renewables, the infamous "duck curve", and DER fundamentals.

Part 2 dives into the practicalities: the flywheel of distributed energy markets, ensuring grid stability, and monetizing this complex system.

We've packed in real-world case studies showing how utilities and tech companies are already leveraging DERs for a more flexible, resilient grid.

Whether you're a utility exec, cleantech nerd, or policymaker, this guide will equip you to navigate the next steps of the DER revolution.

🌊Let’s dive in

Join the Climate Drift Accelerator and accelerate your climate journey. We are selecting people for our next cohort now, and we're looking for talented individuals like you to make a real difference.

🚀 Apply today: Be part of the solution

Meet our guides for today: Maura White, a Climate Drifter and marketing pro bringing fresh perspectives on climate solutions, and Chris Bernkopf, a DER expert and climate tech founder revolutionizing utility management with Podero:

Chris Bernkopf is the Co-Founder and CEO of Podero, an EU-based SaaS platform that enables utilities to synchronize their consumer devices, electricity markets, and software systems to offer highly competitive electricity contracts. He is a serial founder and engineer who previously built a YCombinator backed software company that helps companies like BASF, ABB, and SBB source mechanical parts faster and cheaper. His background is in physics and data science (CERN), as well as in sales and software engineering for the educational AI and electric mobility spaces.

Maura White is a marketing and communications pro with over 15 years of experience across diverse sectors, including technology, media, health, and wellness. She began her career at Edelman working on Fortune 500 companies, including Samsung, Motorola, and Microsoft, and later on for rising startups, like Polyvore and IndieGoGo. She launched Starbucks' first mobile applications with media, and was the first communications lead at Turtle Beach, the leader in gaming audio. Most recently, she has led branding, growth, and awareness campaigns for health equity nonprofits with a strong community impact pillar. Maura's current focus: Exploring climate solutions at the nexus of technology, policy, and equity, driven by her diverse experience and insatiable curiosity.

Introduction

Traditional energy resources and the electrical grid are at a turning point. Fossil fuel energy sources are limited and produce carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions that are affecting the delicate balance of our planet. We are witnessing our climate change as a result of greenhouse gasses. The world will not significantly reduce electricity use, so we must make it completely emissions-neutral, which is only possible if we decarbonize our energy production, electrify everything we can, and synchronize renewable electricity supply and demand – which are in oppositional cycles. Using distributed energy resources (DER) is the pathway to help offset energy supply and demand, and efficiently rebalance the grid. Household DER devices, such as heat pumps, ACs, electric vehicles, and EV chargers, pose challenges for utility operators to predict and orchestrate. However, there are organizations capable of connecting to DER devices on the grid, steering their energy consumption, and increasing green energy consumption at lower cost intervals.

1. Decarbonizing Energy Generation

The World’s Insatiable Need for Energy

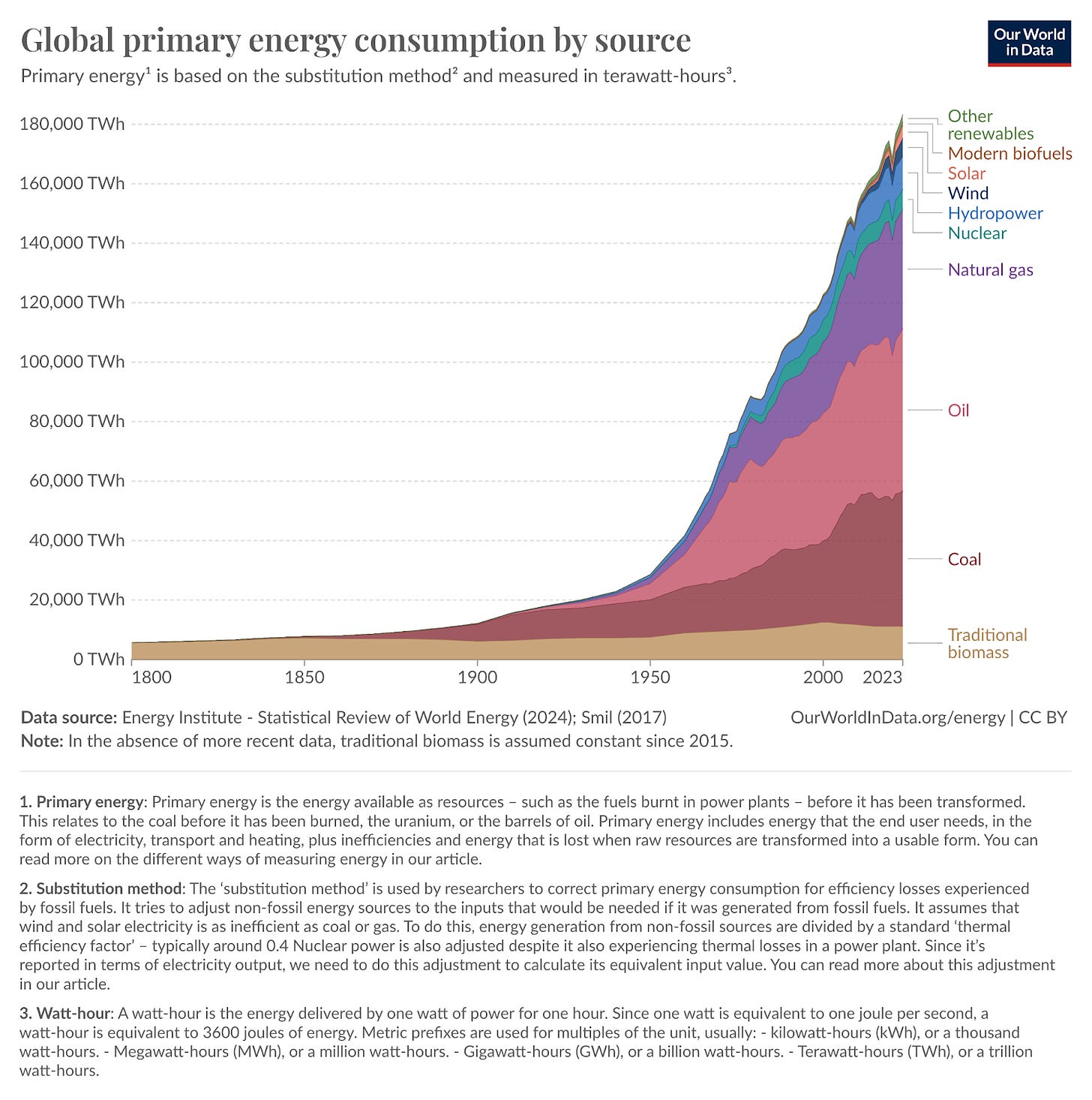

The world’s use of energy is not slowing down. Watt-hours are used to measure quantities of electricity or heat produced. An average household uses about 10,000 kilowatt-hours (kWh) of electricity each year. Global electricity consumption has grown to over 25 terawatt hours (TWh) per year. To help understand that scale of consumption, consider this: A single home needs 1 kWh of energy for one hour, and 1 megawatt (MWh) of energy can sustain 1,000 homes for one hour. A gigawatt (GWh) is equal to one billion watts, and a terawatt is equal to one trillion watts.

Energy is so fundamental to our lives that it’s very challenging to use less of it. Even if one billion people in predominantly high-income countries want to reduce energy usage, their progress in doing so is far too slow to make significant progress toward limiting climate change (1-2% per year). Many of our technologies, such as washing machines, data centers, and hospital equipment, improve our lives in many ways. It would be extremely difficult to separate from our day-to-day usage. Saving energy at individual touchpoints or even at scale cannot get us to net zero, nor will it get us even close. Even when calculated generously, if the European Union were to reduce its energy use by 1.6% every year, it would take almost 40 years to halve its energy consumption.

The 7 billion people in developing countries are within their rights and are on track to achieve higher living standards. That upward trajectory means they will consume exponentially more energy to meet these standards due to a growing population, industrial development, and economic advancement. Global electricity demand is expected to more than double from 25,000 TWh to between 52,000 and 71,000 TWh by 2050, due to the growth in emerging markets’ energy needs and electrification across the economy.

Renewable Pathways to Decarbonizing Energy

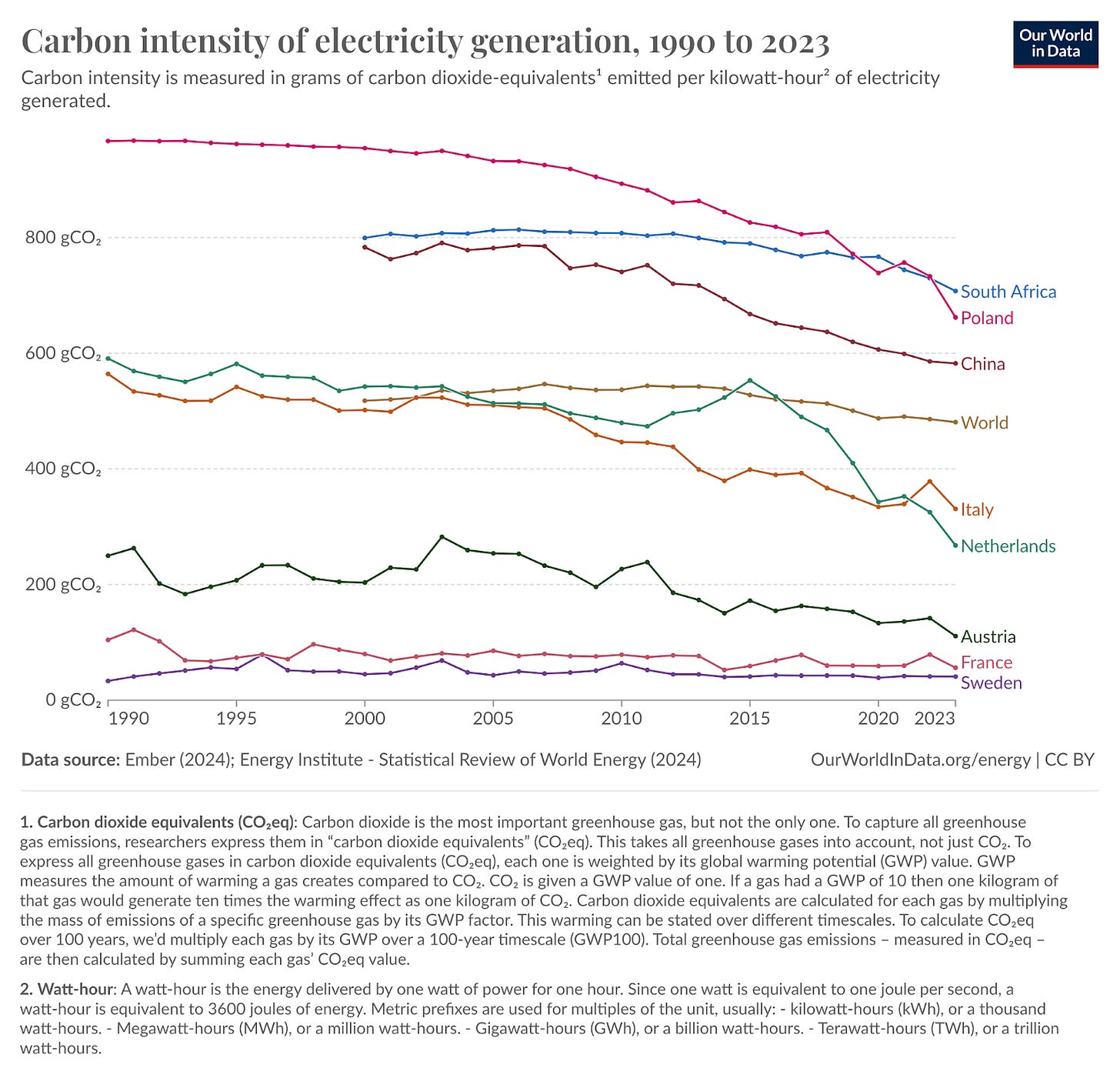

We must quickly decouple energy generation from greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Many governments have set targets for substituting and phasing out fossil fuels, but they still rank highly as the primary sources of most of our energy. Globally, progress to reduce reliance on carbon-intensive energy resources has been slow.

Decarbonizing energy means we have to switch to renewable energy and electrify everything we can when it comes to consumption. Electrification is a crucial tool for reducing greenhouse gas emissions because it offers us the chance to switch renewable energy sources across multiple sectors. To be successful, we also need to synchronize our use of renewable energy across all of our electric devices. If our devices aren’t in sync with available renewable energy sources, we must use some form of non-intermittent, mostly carbon-intensive, electricity generation.

Approximately one-seventh of the world's primary energy is currently sourced from renewable technologies. Generating renewable energy creates far lower emissions than burning fossil fuels. Transitioning from fossil fuels, which currently account for the lion’s share of emissions, to renewable energy is key to addressing the climate crisis. Renewable sources are some of the cheapest forms of energy in most countries, and they create three times more jobs than fossil fuels.

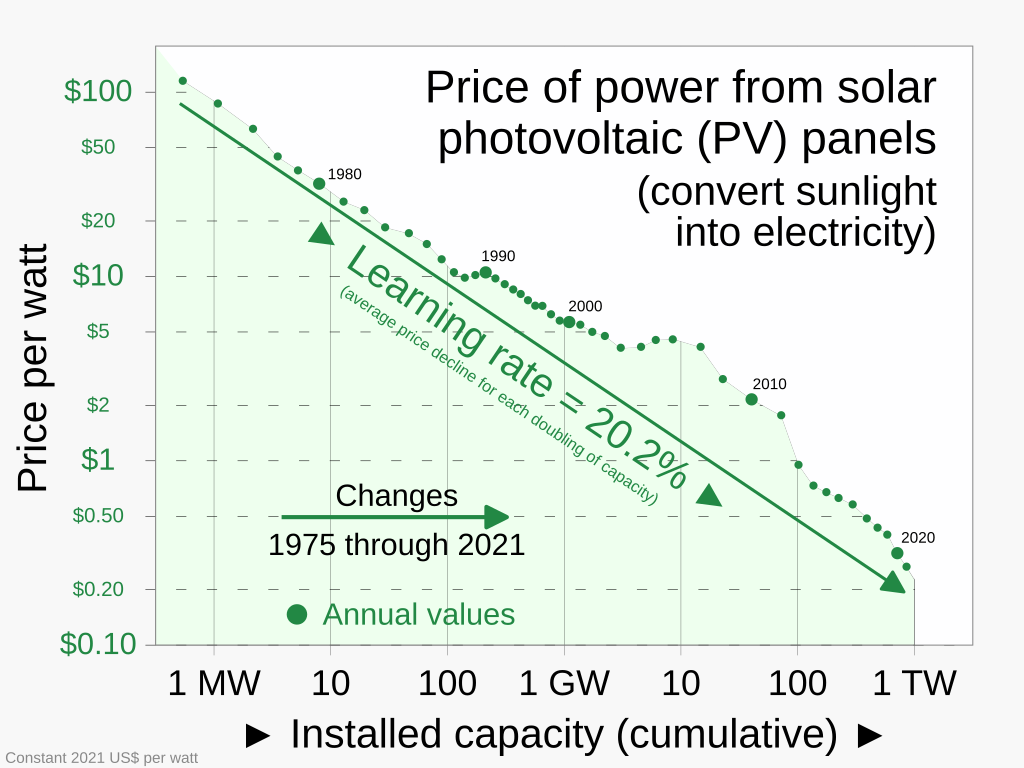

Green, Distributed Power at the Lowest Cost

Solar and wind lead the way as the cheapest sources of energy. Both governments and private entities are rolling out solar at an ever accelerating pace. The cost of solar power production follows Swanson’s Law, named after Richard Swanson, which asserts that the price of solar photovoltaic modules drops 20 percent for every doubling of cumulative shipped volume. Today solar energy is 250 times cheaper to produce than it was in 1976. Rates are likely to continue plummeting faster than experts estimate, as previous estimates were incredibly wrong.

Thousands, if not millions, of tiny tweaks to solar over the period of 45 years has led to serious cost reductions. As wind and solar technologies improve and the cost of their production goes down, it’s extremely difficult for nuclear or gas energy sources to compete financially. This is because any changes to nuclear or gas generation systems take years to complete versus the shorter iterative cycle to make improvements to solar or wind technologies.

While clean energy sources account for 20 percent of final energy use globally, renewables’ share in the world’s power mix is expected to more than double in the next few decades. With this surge of new energy sources our electrical infrastructure requires a boost in flexible capacity to ensure security of supply and a balanced grid. The complete switch from fossil fuels to renewables such as wind and solar will reduce overall energy prices by 23 percent at current prices. As prices for solar and wind most likely continue to reliably fall, the price reduction may turn out to be even larger.

As we shift to clean energy, we are also replacing, or electrifying, devices that rely on fossil fuels. There would be no point in us establishing and accessing green energy to then use devices that produce emissions. Broilers, furnaces, stoves, and vehicles are all examples of devices that are now electrified so that we can heat our homes, cook, or travel from one place to the next without producing emissions.

2. Electrify Everything

The Rise and Challenges of DERs

Distributed Energy Resources (DERs) are small-scale power generation or consumption devices surging through the modern energy system like an unstoppable wave. Unlike traditional power plants or large power consumers like factories, DERs are decentralized and spread out across the energy system.

There are front-of-the-meter (FTM), or utility-side, DERs that operate at a large scale, such as wind farms and photovoltaic solar farms. There is behind-the-meter (BTM), or consumer-side, DER, such as heat pumps, ACs, electric vehicles, EV chargers, consumer-scale inverters, home batteries, microturbines, and fuel cells. There are four ways to use DER: generation, storage, energy efficiency, and demand response.

Generation technologies can be installed anywhere electricity is used, on the distribution grid.

Energy storage can be used to shift energy consumption to times of low demand, supply power back to the grid at times of high demand, and help stabilize the grid. Energy can be stored as electrical energy in batteries, heat in heating systems and boilers, or cooled air in buildings and refrigeration systems.

Energy efficiency solutions, such as heat pumps or LED light bulbs, which use far less energy than gas boilers and electric resistance heaters or traditional light bulbs while maintaining the same level of service.

Demand response resources shift energy consumption in response to electricity prices or to support grid stability.

While hundreds of millions exist globally, most aren’t intelligently used to manage the fluctuating electricity they generate and consume. Connecting small household DERs, typically under 10 kilowatts, is challenging for utilities. Larger-scale DERs at the scale of a few megawatts, like wind or solar farms, are more easily integrated into Virtual Power Plants (VPP). Utilities rely on DER technologies to delay, reduce, or even eliminate the need for additional power generation and infrastructure. DER systems can also improve voltage support and local grid reliability.

Flattening the Duck Curve and Reaching Zero Emissions

The switch from traditional power generation methods like coal, gas, hydro, and nuclear has one significant trade-off. Electricity from renewable energy sources like solar and wind is intermittent or inflexible, meaning we can’t generate power from them when their sources – sunshine and wind – aren’t available. This results in too little electricity being produced when demand is high, such as solar energy supply demand after 6pm, and increasing amounts of electricity being produced at times when there is little demand, such as solar energy supply/demand at noon.

The duck curve below is a graphical representation of electricity supply/demand on the grid as renewable solar energy production and demand shifts throughout the day. Renewables like solar and wind cause spikes in production, while new flexible DER devices cause spikes in consumption — unfortunately, mostly at opposite times. As an example, we turn up our heating and plug in our car just as the sun sets. It helps to illustrate the challenges of balancing energy production from intermittent, renewable sources and growing demand for DERs like electric vehicles, ACs, and heat pumps.

We can’t decarbonize our energy use if most of the green electricity production occurs when it’s not needed or if our consumption peaks when green electricity production is at its lowest.

What’s next?

The transition to a clean energy future is not just a technological challenge, but a systemic one. As we've explored in this first installment, the proliferation of renewable energy sources and the emergence of Distributed Energy Resources (DERs) are fundamentally reshaping our energy landscape.

The intermittency of renewables, exemplified by the duck curve, presents significant challenges. However, it's clear that DERs offer a powerful set of tools to address these issues, potentially flattening demand curves and enhancing grid resilience.

The implications of this shift are profound. We're moving from a centralized, unidirectional energy system to one that's decentralized, bidirectional, and increasingly complex. This transition demands new approaches to grid management, market structures, and consumer engagement.

In Part 2 we dive deep into the practicalities of this:

Generation is Now Inflexible, But Consumption Now IS Flexible

The Flywheel of Distributed Energy Markets

Ensuring Grid Stability Using DER

Connecting, Steering, and Optimizing Power

See you in Part 2:

Blueprint for Steering Distributed Energy Resources - Part 2

Welcome to Climate Drift - the place where we dive into climate solutions and help you find your role in the race to net zero.

So excited for this piece!

Is this the first CDCACC?

(Climate Drift Career Accelerator Challenge Collab) i.e. double byline?

Congrats and thanks, Maura and Chris!