Welcome to Climate Drift - the place where we break down climate solutions and how to find your role in the race to net zero.

If you haven’t subscribed, join as one of our first 1,000 readers by subscribing here:

Hey there 👋

Skander, here.

As we delve deeper into the Carbon Removal Hype Curve, let's pause for a moment to demystify Carbon Offsets.

Rather than a brief overview, we'll be taking a deeper dive, spanning several parts:

In this initial part, we'll explore the origin of offsets, encompassing both the public and voluntary markets.

Next, we'll shine a light on the numerous problems with offsets.

Finally, we'll observe how the market is currently evolving to solve these problems.

Let’s dive in 🌊

Carbon Offsets Explained: Part 1

An origin Story

Net Zero: only an accounting problem?

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) asserts that by 2030, the world must halve its human-induced CO2 emissions to stand a chance of mitigating the most severe impacts of climate change. By 2050, achieving a "net-zero" balance between emissions and their removal is crucial to uphold this probability.

How do offsets and their accounting fit into the picture?

By standard definition, offsets refer to the reductions in greenhouse gas emissions in one location to counterbalance emissions elsewhere.

Here's a common scenario: Instead of a developed nation or a corporation cutting down its own CO2 emissions, it funds a developing nation to do so, matching the emission amount. If the purchasing entity acquires enough offsets, they often label themselves as 'carbon neutral' or 'net zero'.

You might have encountered this: Say you're booking a flight, and you're given an option to offset your journey's entire carbon footprint for a surprisingly low fee. Sounds too good to be true?

That's because it often is.

In the next part we will dive into the reasons behind this skepticism.

But first, let's trace back to the origins of the offset concept.

Offsets and politicians

Three primary policy strategies can be implemented to significantly decrease net carbon emissions:

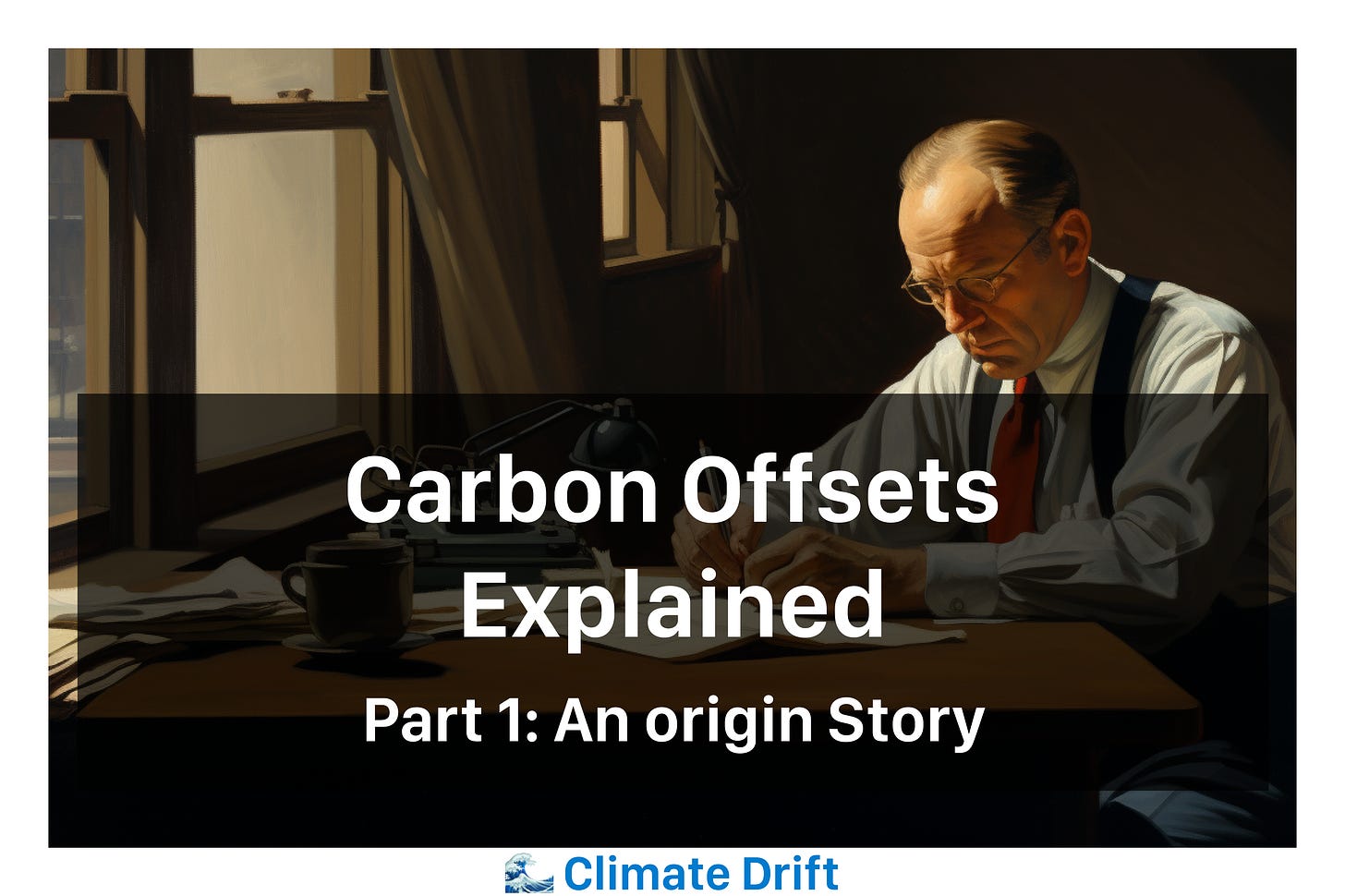

First is Carbon Taxation, which involves levying taxes on activities and products with high carbon emissions. Economists widely believe that carbon taxes are the most effective and efficient method to reduce emissions without significantly harming the economy. To ensure these taxes don't disproportionately burden the less affluent, the revenue generated should be channeled to assist those most impacted by the taxes. Currently, 25 nations have adopted carbon taxes, and 46 countries have established some form of carbon pricing, either through taxes or emission trading systems. However there is a major problem: Introducing new taxes is rarely popular among constituents, making it a contentious issue for elected officials.

Second is Carbon Trading, a system that limits carbon emissions by distributing carbon permits. Carbon trading can foster innovation and reduce costs, making renewable energy and Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) economically feasible. Some trading schemes permit businesses to purchase carbon offsets, either domestically or internationally, to balance out their emissions.

Lastly, Carbon Offsetting refers to actions taken to counterbalance emissions produced in one area by reducing emissions elsewhere. This can be achieved through initiatives like reforestation or by shutting down high-emission sources like coal power plants.

Two primary offsetting frameworks exist: the UN's Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) and the voluntary market.

The CDM supports UN-accredited projects in developing countries that yield greenhouse gas reductions. We will look at this one and its origin first.

History of Carbon Offsets

Today, national or regional carbon trading schemes cover over 13% of global carbon emissions. These systems are operational in countries like the USA, Canada, China, and regions like the EU. However, it's worth noting that the US lacks a national carbon market, with California being the sole state boasting a formal cap-and-trade program.

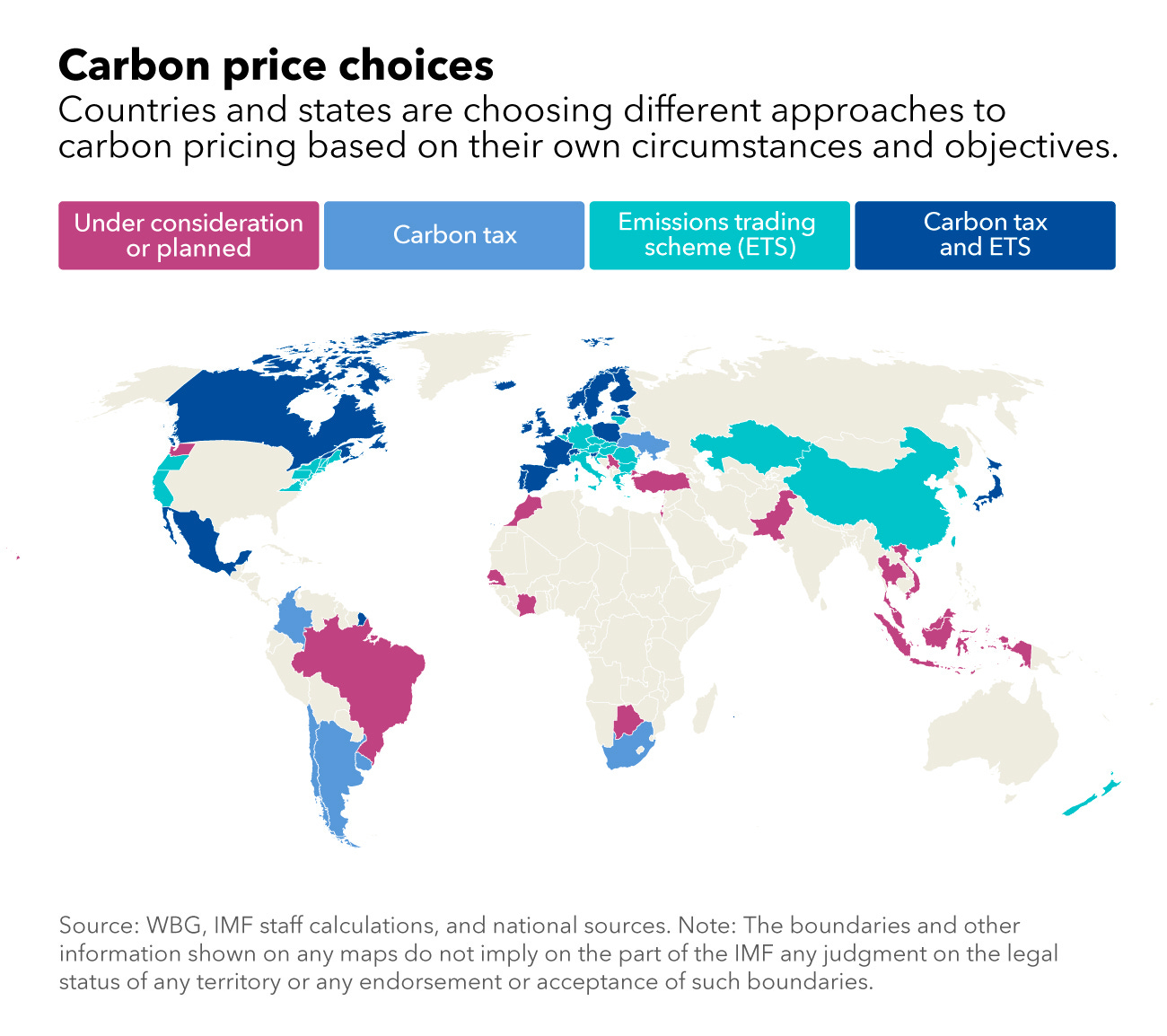

In 1977, the US Clean Air Act pioneered one of the earliest tradable emission offset systems. Under this mechanism, a company could increase its emissions if it compensated by funding a more significant emission reduction at another facility. Fast forward to 1990, amendments to the Act birthed the Acid Rain Trading Program, introducing the "cap and trade" concept.

Here, emission limits for pollutants would gradually tighten, but within these confines, companies could trade offsets resulting from emission-reducing investments.

And it did work out: A shining example is the US's success in curbing sulfur dioxide and N2O emissions with the Clean Air Act . While initial projections estimated a $7.4 billion cost, actual data in 1998 revealed it was under $1 billion.

Carbon trading has thus garnered significant attention from policymakers, with many championing regional or global trading systems. If it worked for SO2 and NOX, why not for the other greenhouse gases?

Introducing: Clean Development Mechanism (CDM)

In the early 2000s, carbon offsets gained momentum with the introduction of the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) by the UN.

Established under the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, an international climate agreement, the CDM is an offset scheme aimed to assist developed nations in achieving their greenhouse gas reduction targets. At the same time, it promoted sustainable growth in developing countries.

As outlined by the UN, the CDM enabled nations with emission-reduction objectives to partially fulfill these commitments by purchasing Certified Emission Reductions (CERs). Each CER corresponds to a reduction or avoidance of one tonne of CO2 emissions in developing nations.

For instance, if Germany pledged to cut emissions by 100 million tons (MT), they could invest in a renewable energy project in China projected to offset 10 MT. This would mean Germany would then only need to curtail their domestic CO2 emissions by 90 MT to achieve their target.

Spotlight on Europe:

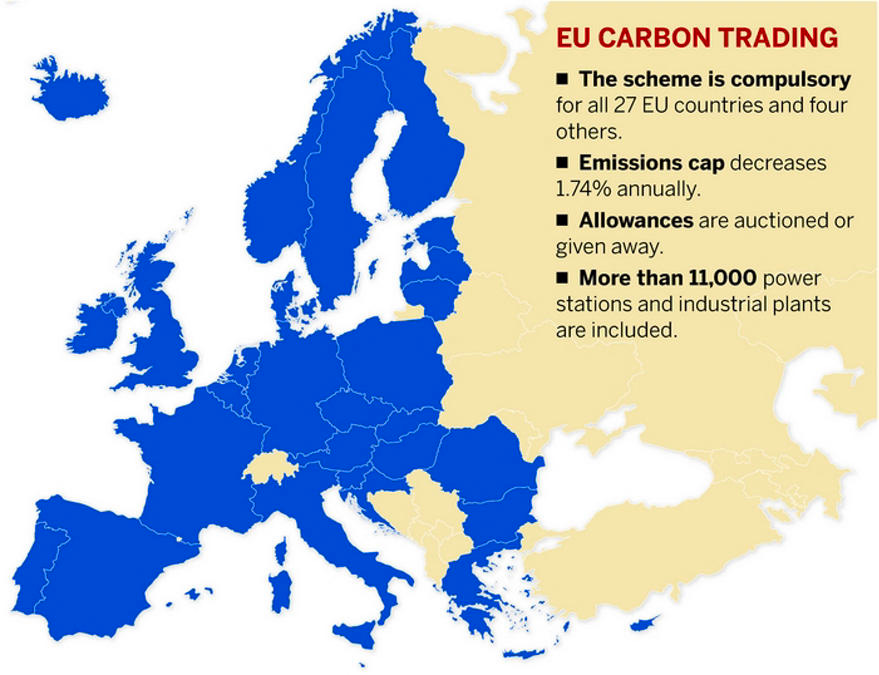

The European Union's Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) is a beacon in the world of carbon trading, boasting the title of the most extensive and seasoned system of its kind. The ETS is comprehensive, covering sectors from electricity generation to various manufacturing industries like pulp, paper, and glass. Its reach is impressive, operating across 31 countries, which includes all 28 EU member states and extends to Iceland, Norway, and Liechtenstein.

In terms of its impact, the ETS addresses a significant chunk of the EU's emissions, handling half of its CO2 output and 40% of its total greenhouse gas emissions.

The system operates on the 'cap and trade' model. Here's how it works: a ceiling is set for greenhouse gas emissions for each country's installations. These installations are then given emission 'allowances', which can either be auctioned or allocated freely, and these allowances can be traded. The installations have a responsibility to ensure their emissions don't exceed their allowances. If they do, they need to buy more. If they've been efficient, they can sell their surplus.

The ETS has evolved in phases: 2005-07, 2008-12, 2013-20, and 2021-30. With each phase, the system has tightened its grip, reducing the available credits and roping in more sectors. This progressive approach aims to drive rapid emission reductions.

However, no system is without its critiques. Detractors have pointed out issues like over-allocation, windfall profits, price volatility, and, more broadly, the system's failure to meet its primary objectives:

The initial lack of governance and oversight led to some unintended consequences. The system inadvertently incentivized actions that, while technically within the rules, didn't align with the spirit of environmental conservation. A glaring example was the production and subsequent destruction of fluorocarbons (like those found in refrigerators). These compounds are potent contributors to global warming. The ETS allowed companies to claim credits for destroying them. However, it didn't prevent companies from producing these harmful compounds solely to destroy them later, essentially gaming the system. This loophole led to a bizarre situation where factories would produce these harmful gases only to destroy them at the end of the production line, ironically emitting more greenhouse gases in the process.

Despite these challenges, the EU ETS has had its successes. A 2023 study highlighted a commendable 10% reduction in carbon emissions from 2005 to 2012, without any negative impact on the profits or employment of regulated firms. By February 2023, the price of EU allowances even soared past 100€/tCO2 (equivalent to $118).

Supporters argue that the initial phase (2005-2007) of the EU ETS was more of a "learning phase." It was designed to set benchmarks and lay the groundwork for a carbon market, rather than achieve drastic emission reductions. This perspective underscores the importance of iterative learning, as described in How Solar Got cheap:

What about the voluntary market?

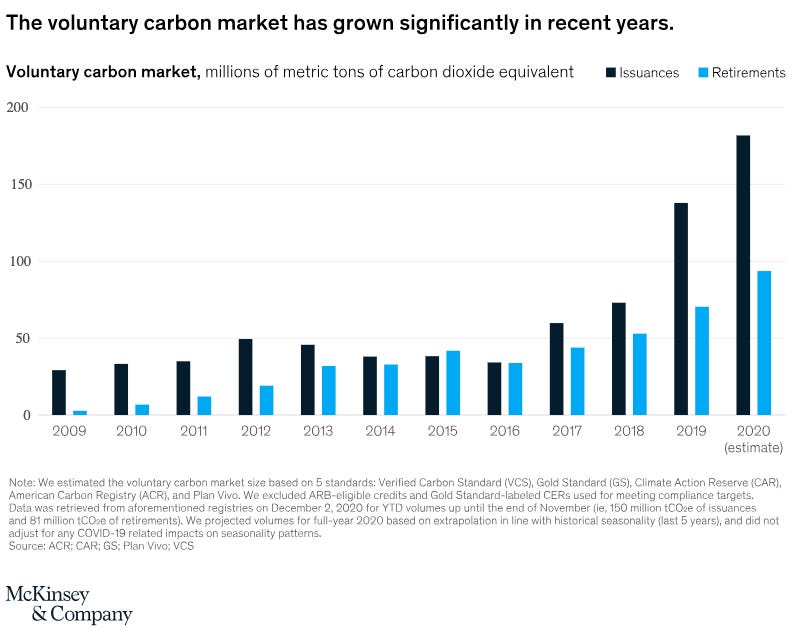

What's surprising about the voluntary carbon market is that despite the significant media coverage, it remains relatively small in scale. In fact, the total amount of offsets from 1988 to 2005 was about $300 million. Since then it has grown: Last year, in 2022, its transacted value was a few billion dollars.

In stark contrast, the compliance markets are valued at approximately $850 billion, with the European emissions trading scheme being a dominant player.

The voluntary market however operated without regulations, and history shows that unregulated markets often spiral into a race to the bottom.

Imagine being a major corporation aiming for Net Zero. If one vendor offers you a quality carbon offset from Brazil at $20 a ton, but another pitches it at $5 a ton, which would you choose?

This setup creates a skewed market dynamic. Sellers are driven to undercut prices, while buyers are on the hunt for the cheapest deal. In this equation, there's no motivation for either party to prioritize quality. Without regulatory oversight or penalties for subpar offerings, both sides are incentivized to compromise on quality in favor of cost savings.

Enter: Carbon Neutral Marketing

Over time, carbon credits evolved to serve a new purpose, which can best be described as "brand storytelling." Instead of purchasing credits primarily for compliance or tax benefits, companies began acquiring them for marketing advantages. By buying these credits, businesses could proclaim a status of carbon neutrality, prominently displaying this commitment on their vehicles, advertisements, and product labels. This became their unique selling proposition derived from the credits.

This trend continues today. Consider the numerous airlines offering passengers the option to offset their carbon footprint for a nominal fee, calculated based on the flight distance.

Time to set standards

As an economist, I appreciate the market's innate ability to self-regulate [Disclaimer: One of my editors pointed out that I should point out that his is irony].

This manifested itself in the carbon credit arena with the emergence of multiple standard-setting bodies, each striving to elevate beyond the foundational blueprint of the CDM for the voluntary market.

Among these, two entities stand out: Verra, which is perhaps the most recognized, and the Gold Standard.

In the next part we will start by looking at the failure of these standard bodies to set good standards, leading to the Great Carbon Offset Scam.

As we delve deeper, it becomes evident that while carbon offset systems offer potential, they grapple with significant challenges, especially concerning governance and oversight. The voluntary market, though smaller in scale, underscores the perils of a laissez-faire approach. Here, the quest for cost-efficiency might eclipse the overarching objective of authentic carbon reduction.

Armed with this historical context, we'll now explore the problems with offsets.

Let's dive in.

Skander

PS: Help Climate Drift grow by sharing this post.