How can we incentivize safe & durable geostorage? - Part 1

Understanding Carbon Capture and Geological Storage

Welcome to Climate Drift - the place where we dive into climate solutions and help you find your role in the race to net zero.

If you haven’t subscribed, join here:

Hey there!

Skander here!

Today we are starting with Part 1 of a two-part deep dive, exploring a critical but often overlooked climate solution: geological carbon storage & how to make it feasible.

I already wrote a lot about the carbon removal hype, including the largest climate acquisition last year.

Part 1 sets the stage by unpacking the complexities of Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage (CCUS) projects, with a focus on Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) technologies. We'll explore:

The need for CDR to meet Paris Agreement goals

The intricacies of carbon capture, transportation, and storage

The potential and challenges of geological storage (geostorage)

The current state of the CDR market and its projected growth

We'll dive into the technical aspects of geostorage, the importance of proper site selection, and the often-underestimated complexity of this crucial step in the CDR process.

🌊 Let’s dive in

Join the Climate Drift Accelerator and accelerate your climate journey. We are selecting people for our next cohort now, and we're looking for talented individuals like you to make a real difference.

🚀 Apply today: Be part of the solution

Meet our guide for today:

Kim Vinet, a geologist turned sustainability expert and carbon market advisor (and happy Drifter), bringing a unique perspective on climate solutions and the future of energy:

Kim is the founder of Affirmative Sustainability, a consultancy she established in 2020 to help corporations navigate the complex landscape of international policy, climate reporting, and disclosure frameworks. With nearly two decades of experience spanning the energy sector, policy development, and carbon markets, Kim now focuses on low-carbon economy transition planning and carbon market advisory for both private and public clients.

Her journey began as a geologist in the petroleum industry, giving her firsthand insight into the fossil fuel production. This background, combined with her passion for nature as a former professional skier and ski guide, fuels her commitment to environmental protection and sustainable solutions.

Kim's expertise covers the entire emissions lifecycle, from petroleum production to carbon offset project development and strategic advisory on carbon market economics.

Introduction – Who am I?

Hi all! I’m Kim. I am a geologist by training and while I focus on sustainability and carbon market advisory these days, I started my career almost 20 years ago as a geologist in the petroleum industry. Most folks find it hard to believe that incredible attention to detail goes into understanding the reservoir dynamics that result in responsible fossil fuel production. Turns out though, that even the most responsible petroleum production results in high atmospheric carbon – and we’ve known that for a very long time.

I am a naturalist at heart. As a retired professional skier and ski guide, I have worked and recreated in some of the planet’s most beautiful yet fragile and climate-affected regions – polar, alpine, and glacial ecosystems. I have become deeply connected to our natural world and have also had the privilege of leading those experiences with others. That connection to the planet and each other is a massive driver of impact in my (other) professional life.

I have been involved in every aspect of the emissions lifecycle from the creation of emissions through petroleum production, subsurface evaluation and reservoir engineering, and across the carbon dioxide removal landscape through carbon offset project development, measurement & verification (of petroleum reserves, greenhouse gas emissions and offset project methodologies), credit registration, policy development, and strategic advisory on carbon market economics, commercial negotiation of carbon contracts, offset procurement strategy, implementation, and pricing. Most professionals become extremely specialized in one area but because I have been there every step of the way, I have had to think critically about how CDR players interact and what is preventing financial incentives to perform geostorage activities.

TLDR – Imagine a climate solution that could transform petroleum industry operations from hydrocarbon extraction to emissions sequestration!

We know that today, fossil fuels account for >75% of global GHG emissions (that’s over 40 GtCO2e annually). We need to use every tool available to decrease the emissions in our atmosphere. Many people talk about novel carbon dioxide removal (CDR) technology perpetuating the use of petroleum products, but what if certain carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) projects instead played a major role in transitioning petroleum operations away from extraction?

Geological storage (geostorage) of the carbon dioxide (CO2) removed by novel CDR technology is a crucial tool for permanently reducing global emissions. Petroleum industry practitioners have dedicated years to understanding subsurface reservoirs, but there is no financial value assigned to identifying geostorage capacity. To achieve efficient, safe, and durable emissions reductions through novel CDR projects, there must be financial incentives for experienced subsurface operators to get involved.

It is possible to create robust measurement, reporting, and verification that will enhance the safety and credibility of geostorage projects but it has not yet been established. Relationships between those who remove emissions from the air and those who store them will require a comprehensive definition of ownership boundaries, scope, and liability as well as sound regulatory control. Within CCUS projects, the focus has been placed upon the novel CDR technology. Conversations tend to end with “...and then we put the emissions underground” and the transportation and geostorage components are often overlooked.

With a lack of foresight and planning, captured emissions are injected wherever the nearest landowner is willing to partner up, potentially exposing the project to liability and permanence risk. Carbon capture technology developers have started to appreciate revenues through the sale of carbon offsets, but very little of that has been transferred to the subsurface operator. Effective due diligence over the subsurface is the missing link that will facilitate safe and durable geostorage but we need a financial incentive.

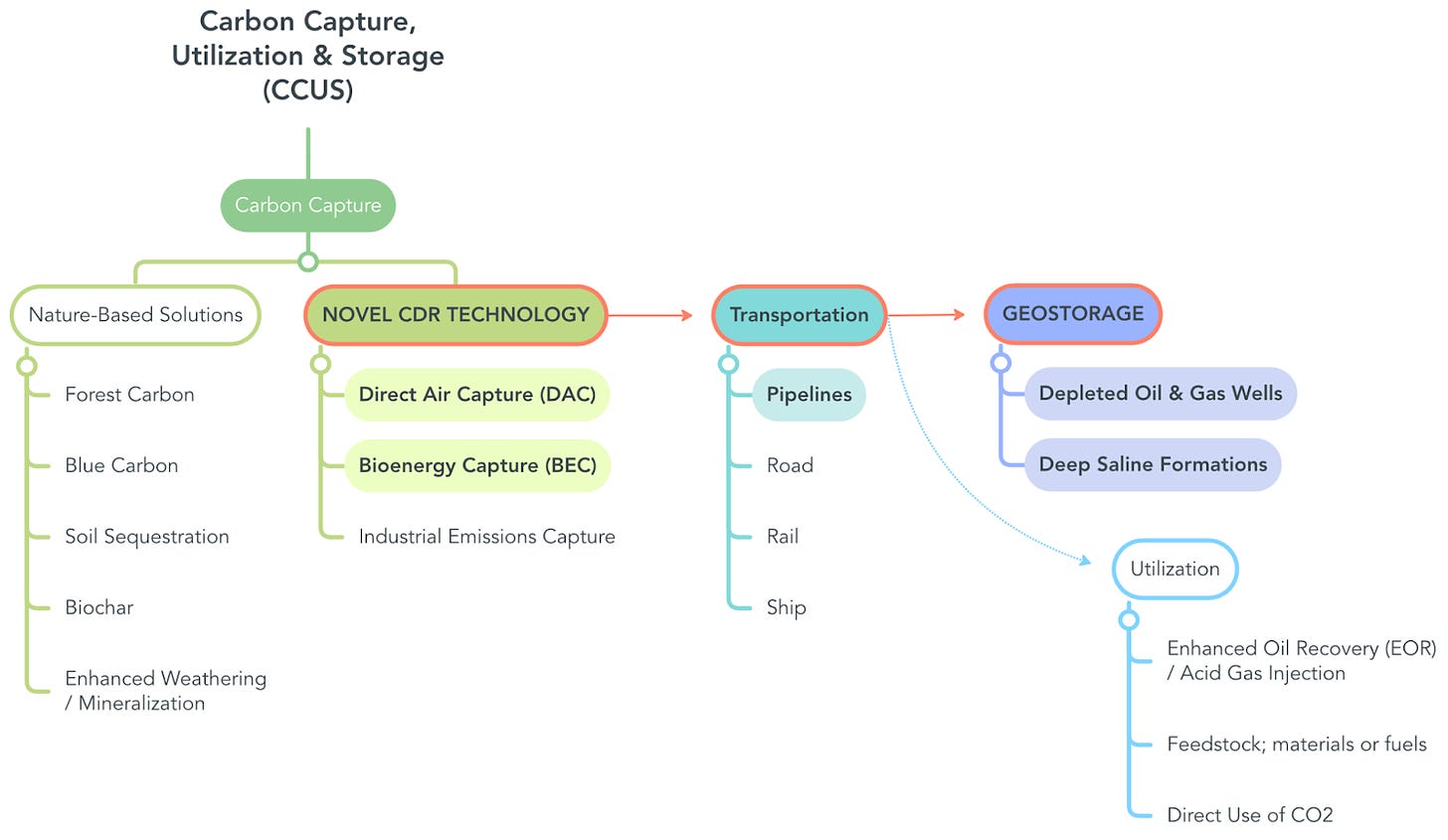

CCUS refers to Carbon Capture Utilization & Storage projects. This article refers solely to the emissions extracted through the novel Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) technologies of Direct Air Capture (DAC) or Bioenergy Capture (BEC), which are subsequently transported and injected into depleted oil & gas wells or deep saline aquifers for permanent geological storage.

For context, nature-based CDR solutions, CO2 utilization projects or any scheme that perpetuates the use of fossil fuels (such as point-source industrial emissions capture) are not included.

Impact and scale of emissions reductions

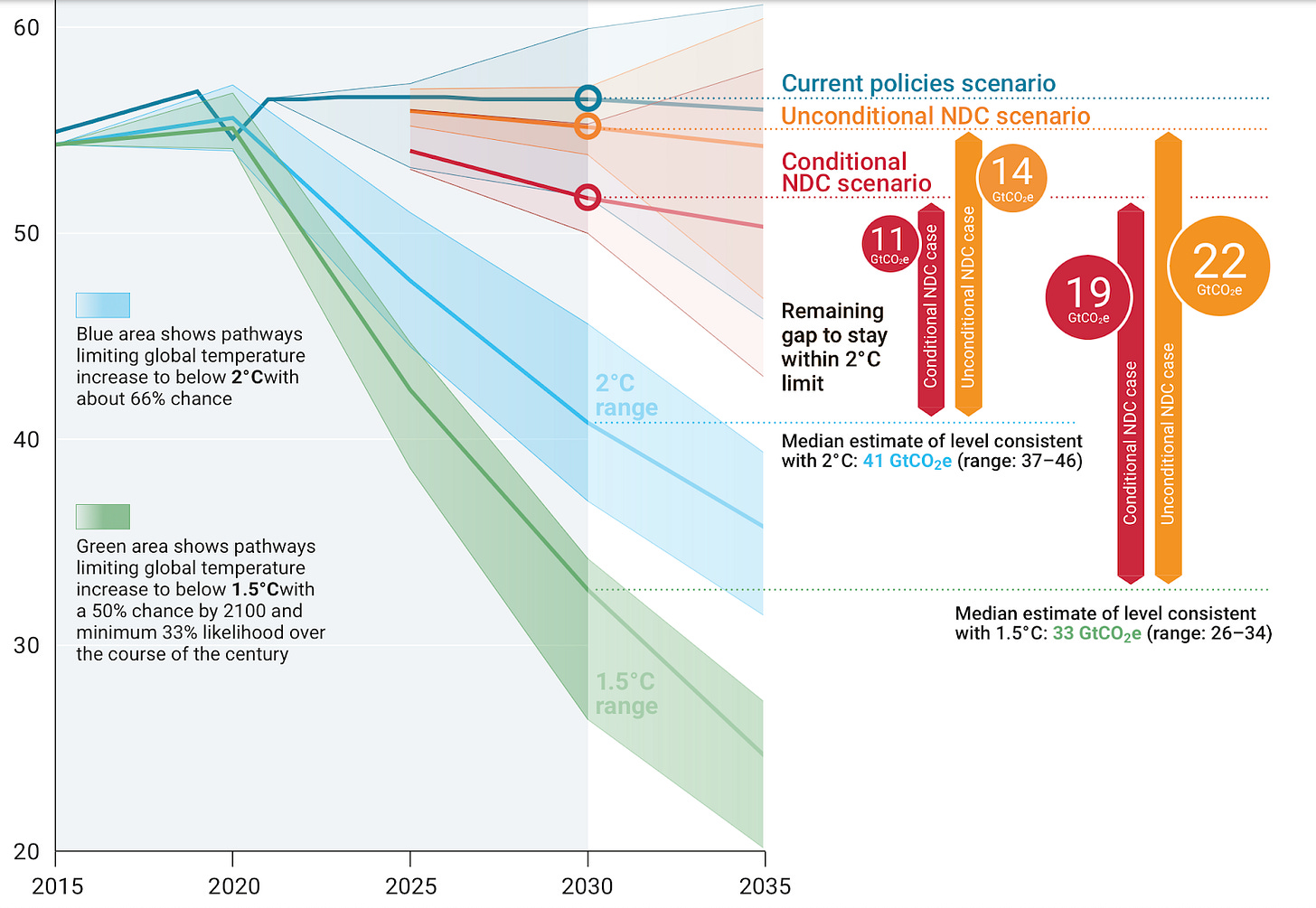

According to the UN Environmental Programme Emissions Gap Report 2023, under a +1.5°C by 2050 scenario, novel CDR technology will need to grow to at least 4 GtCO2e of annual removal – the present rate is only 0.002 GtCO2e annually. CDR projects have the potential to fulfill between 10-25% of the goals of the Paris Agreement.

For an appreciable scale of sequestration, there will need to be hundreds or even thousands of large-scale geostorage projects around the world. As novel CDR projects scale, the required CO2 storage volumes will not be fulfilled by known geostorage opportunities, nor do the project developers generally hold the appropriate operational knowledge or assets to create access and increase geostorage capacity. Because oil-bearing reservoirs have been comprehensively studied, we know there is potential for injection and geostorage of emissions at well-characterized and properly managed sites. The high concentration of geoscientists and reservoir engineers working on active petroleum projects could facilitate the transfer of knowledge and leading operational practices from petroleum extraction to emissions sequestration.

Deep saline formations are widespread globally and are believed to have by far the largest potential for geostorage; very likely >1000 GtCO2 (some studies suggest it may be an order of magnitude greater). Saline aquifers offer relatively little commercial value for petroleum producers so limited CO2 injection into deep saline formations has occurred to date. Quantifying geostorage capacity in deep saline formations is difficult until additional operations begin to substantiate operational assumptions. The United States Geological Survey reports that “Evaluation of the CO2 storage capacity in deep saline aquifers is very complex…” (more on this later).

Studies indicate that depleted petroleum wells (many of which are still operated by petroleum companies) could be used to store around 45% of projected CDR activities by 2050. Also according to the IPCC, depleted oil and gas reservoirs are estimated to have a global storage capacity of approximately 675–900 GtCO2 (though these wells occupy only a small fraction of the pore volume that could be used for geostorage).

Some industrial operators have initiated CCUS projects using point-source emissions capture (i.e. capture of CO2 from hydrocarbon, ethanol, or hydrogen production facilities). In jurisdictions with carbon pricing, some facilities can reduce their compliance costs by applying the carbon credits associated with CCUS to their industrial emissions cap. CCUS credits have thus far been marketed for sale based on the related capture technology. Point source CCUS projects are not commonly considered CDR projects since they do not result in net-negative atmospheric carbon.

What is Carbon Capture, Utilization & Storage?

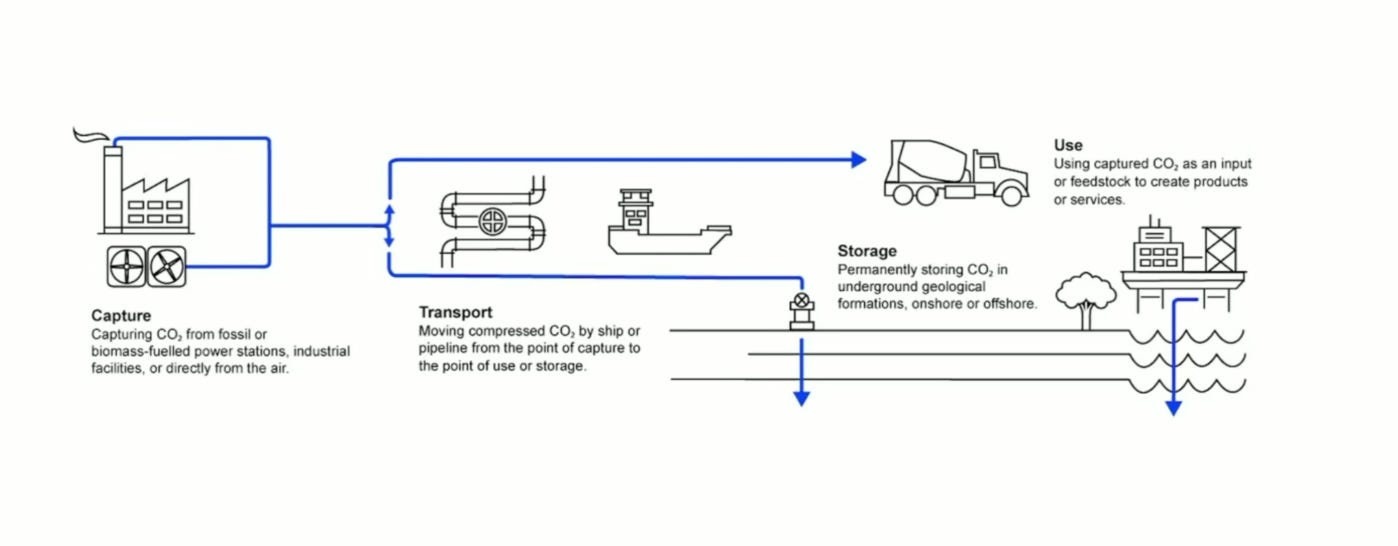

Carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) projects remove CO2 from the atmosphere and either use or permanently store the captured emissions. Successful projects permanently remove and store emissions for up to thousands of years, resulting in a net-negative carbon footprint.

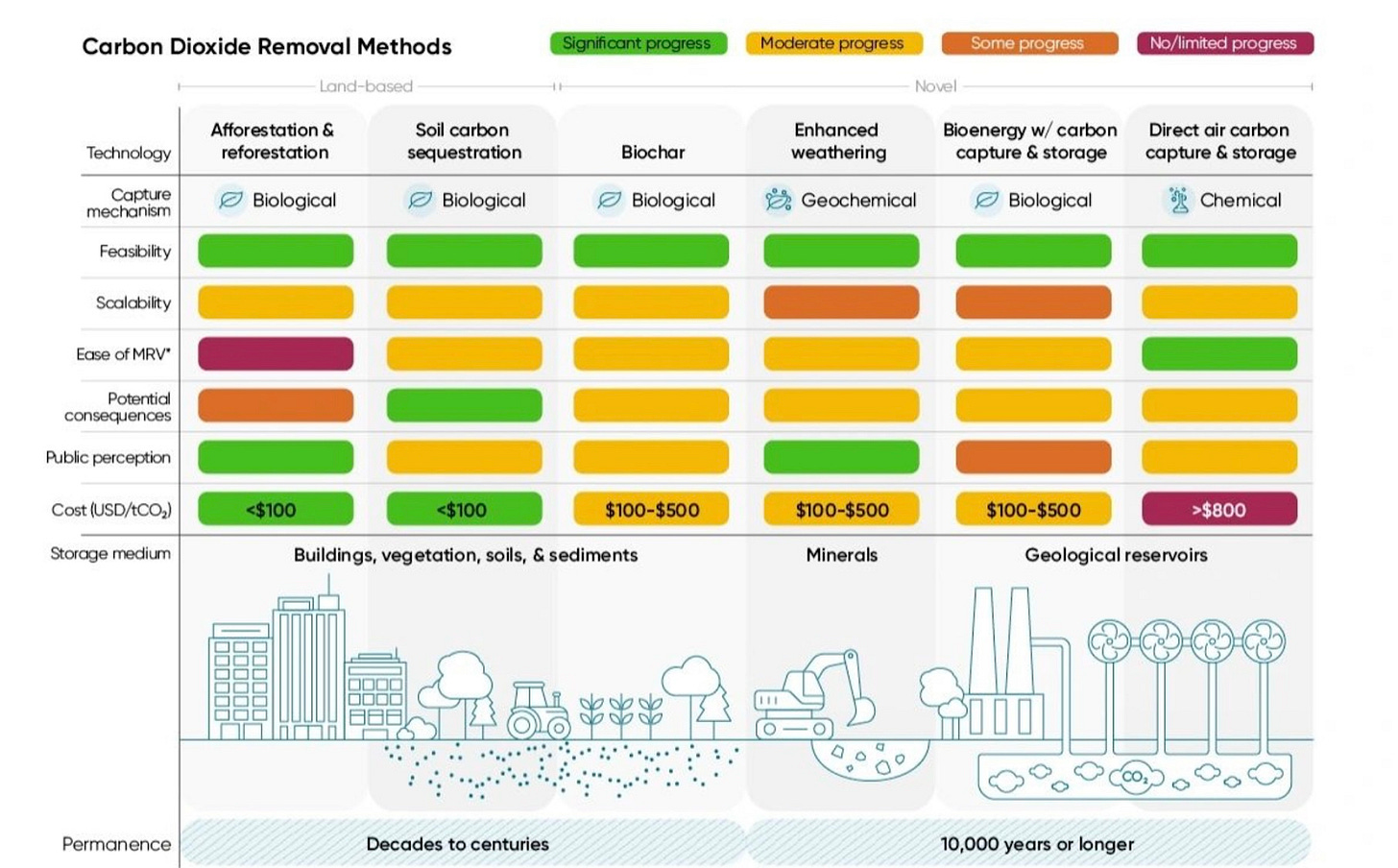

A combination of abatement (the reduction of operational emissions) and CDR activities will be necessary to achieve our global net-zero goals. CCUS projects should complement and not replace efforts to reduce operational GHG emissions. CDR projects are divided into nature-based and technology-based solutions. Nature-based solutions optimize the Earth’s natural systems (forests, soils, rock, and oceans) to store carbon, while novel CDR technologies utilize human-built infrastructure to physically remove CO2 from the air. Common novel CDR project types are:

Direct Air Capture (DAC) – technology that filters emissions from ambient air

Bioenergy Capture (BEC) – emissions capture from bio-fuelled power stations (enabling clean energy)

Industrial Emissions Capture – point-source emissions captured directly from fossil fuel power plants or industrial facilities. Emissions remain net positive as primary emissions are only avoided and utilization results in secondary emissions, as well as perpetuating or enabling fossil fuel production.

Nature-based solutions account for more than 99.9% of CDR projects that are in operation today (due to lower associated costs and ease of implementation). Novel tech projects (especially DAC) have the highest implementation costs (often >800 USD/tCO2e). While the market for nature-based solutions is more mature, public perception is low after recent issues with project measurability and verification. Nature-based solutions also have generally decreased durability due to exposure to physical risks (such as volatile weather, wildfire, or regulatory changes). Because carbon storage is built into nature-based solutions, they do not face the same physical barriers as tech-based solutions when transporting captured emissions to a storage site. There is often a physical distance between the capture site and the usage or storage site, which creates a transportation discrepancy that can reduce project viability and add substantive costs.

The CDR market is expected to reach 2 billion USD by 2031 and could become a trillion-dollar industry by 2050. In 2022, the global CDR market was valued at 462 million USD and transaction volumes had expanded 10% year-over-year. In the second quarter of 2024, year-over-year transaction volumes were up 18%, and an all-time high of 4.8 million tCO2e of CDR credits were transacted. Between 2020-2022, the majority of projects were forest-based projects, whereas more recently, Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS) projects have made up over 90% of the transacted volumes. Microsoft was solely responsible for 91% of the total CDR transaction volumes in Q2 2024 and now represents around 75% of the all-time volume of contracted durable CDR.

On July 9th, (Q3) 2024, 1PointFive, announced that it signed the largest-ever DAC-based CDR credit purchase agreement to deliver 500,000 tCO2e of CDR credits to Microsoft over the next six years. Globally, there are now 16 DAC facilities in advanced development, which could provide around 4.7 MtCO₂e of annual removals by 2030. But to reach 2050 net-zero targets, estimated DAC deployment will need to reach 75 MtCO₂e/yr by 2030 and upwards of 980 MtCO₂e/yr by 2050. As of 2022, the capacity of DAC plants in operation worldwide was still in the range of thousands of tons, accounting for just 2.5% of total CDR transactions.

Geostorage

Geological storage or “geostorage” describes the capacity of subsurface reservoirs to permanently hold or sequester emissions. Appropriate geostorage reservoirs hold fluids (both liquids and gasses) within the pore spaces of rocks that have become buried deeply underground. The strong credibility of novel CDR projects largely stems from the high likelihood of permanence associated with geostorage, yet the importance and complexity of geostorage have been widely underestimated.

Popular perception is that ‘caverns’ or massive structural void spaces exist underground — this couldn’t be further from the truth. The occurrence of large underground caverns is exceedingly rare. There are multiple methods of geologically storing CO2:

Mineralization – traps carbon within reactive rock formations such as basalts, to form stable minerals or through a chemical reaction that produces carbonate (CaCO3) minerals such as limestone, marble, or chalk.

Dissolution – when CO₂ dissolves in water, it can form carbonic acid (H₂CO₃), which is a weak acid that can dissolve salts or absorb into solution within the fluids that are present in the reservoir pore space.

Unmineable Coal – CO2 molecules are attracted to and weakly bind to particles on the surface of organic matter within coal and shale. This is a reversible process that depends on temperature and pressure.

Trapping – fluids migrate through the pore spaces of the storage formation (geological reservoirs) but are trapped below an impermeable, confining layer (caprock).

Though there are instances of geostorage within fractured igneous or metamorphic rock (where fluids are transmitted through or stored within fractures), the IPCC Special Report on Carbon Dioxide Capture and Storage (SRCCS) says that CO2 storage in depleted oil and gas reservoirs is very promising because they are well understood and significant infrastructures are already in place, and deep saline formations are believed to have by far the largest capacity for CO2 storage and are much more widespread than other options. There are many sedimentary basins globally that would facilitate geostorage. Because these same basins are also the source of petroleum exploration, geostorage sites are often located in the same region as many of the world’s emission sources.

The underground storage of natural gas and as well as acid gas injection operations in the petroleum industry have indicated that CO2 can be safely injected and stored at well-characterized and properly managed sites. In North America, geoscientists have studied hundreds of thousands of well bores that were drilled over the past ~150 years within the conventional reservoirs of the Western Interior Sedimentary Basin (WISB). There is vast understanding of the location, size, scale, depth and production potential of petroleum reservoirs across the basin.

How much CO2 can be stored depends upon myriad reservoir and fluid factors, including rates and gradients of pressure, temperature, saturation, solubility, density and chemistry, fluid flow dynamics, reservoir porosity and permeability, the presence of other fluids or inconsistent mineralization within the reservoir, injection rates, the depth and thickness of the reservoir, proximity to freshwater aquifers, proximity to surrounding wells and reservoir infrastructure and proximity to sensitive ecosystems or communities.

Defining geological characteristics and reservoir boundaries will allow us to understand the safety and durability of sequestration. To better evaluate the feasibility and location of the most effective geostorage sites, we need to emphasize the following questions:

How well can we predict reservoir shape and size?

Which reservoir dynamics will affect the injected fluids?

What technologies, infrastructure and monitoring controls are currently available for geostorage?

How does the regulatory and legal environment enable the project?

How do project economics affect feasibility?

How are we managing knowledge gaps or uncontrolled risks?

Transportation, access & ownership

Transportation of CO2 from the capture site to an appropriate geostorage site is another factor that has largely been overlooked. To complete CDR activities, the emissions that were removed from the atmosphere must become permanently stored. Selecting a geostorage site that is close to the CDR facility has thus far taken precedence to maintain low transportation costs.

Transportation to the geostorage site requires the operator to legally possess access rights. Not only does this mean that surface land leases or ownership must be attained, but in certain jurisdictions (like Canada), subsurface or mineral rights must also be obtained. CO2 injection operations can also require significant land and water resources that may compete with food production, biodiversity conservation, or other activities prioritized by Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPLCs) and require development of the relationships between operators, rights holders, and land owners. This often creates associated opportunities to increase operational efficiency and project optimization. Each time the captured emissions change hands or change state, a financial transaction often also takes place and the transfer of ownership must be defined by legal documentation.

For efficient geostorage, emissions are compressed into supercritical CO2 (at depths of 800-1000m, CO2 encounters temperatures and pressures that result in a constant, liquid-like, “supercritical” state). Emissions can be transported as a viscous fluid or are compressed into supercritical form at the surface, which requires gathering and compression facilities. Petroleum companies commonly own and operate these and other facilities, along with pipelines, wellbores, and injection equipment. CO2 can also be shipped by rail, truck, or marine transportation.

Utilization

For many, the mention of “carbon capture” conjures images of emissions utilization schemes such as enhanced oil recovery (EOR) that increase fossil fuel production. EOR has taken precedence as an economically feasible way to sequester emissions since income is generated through oil production – but we are all well aware that increasing fossil fuel production is no way to reduce emissions over the long term. Emissions utilization in the form of EOR or CO2 used directly or as a feedstock (embedded in materials or fuels) are not destined for permanent geostorage and often do not decrease atmospheric CO2 concentrations (though permanence of sequestration is dependent on usage type).

Sequestration Hubs

are clusters of facilities that share the same CO2 sequestration infrastructure for emissions capture, transportation, utilization, or storage. Benefits of shared infrastructure include:

lower costs (by creating economies-of-scale)

additional options for management or sharing of risks

government support to strengthen regional visibility

collaboration across industries that don’t normally work together

Sequestration hubs are generally located in areas of significant industrial activity that also have favourable geostorage capacity. Active sequestration hubs are situated off of the Gulf Coast and in the Midwest of the United States, the North Sea, and the Netherlands in Europe, Australia, Asia, and the Middle East. Many sequestration hubs are currently associated with point-source industrial emissions capture and EOR (further increasing their economic viability). However, sequestration hubs could also promote permanent geostorage within deep saline aquifers, which would not exacerbate the emissions problem.

Recent developments in Canada:

In 2022, the AB government selected 25 projects to begin exploring how to develop environmentally safe carbon storage hubs and has recently announced its first carbon sequestration agreement. Alberta is also exploring other carbon storage scenarios and is now accepting applications for small-scale and remote carbon storage projects. By 2035, CCUS development in Alberta is expected to:

generate approximately $35 billion in investment

add up to 21,000 jobs.

Carbon Crediting

To sell carbon offset credits, projects must be “additional” meaning that the CDR activity only becomes financially viable after receiving income through the sale of carbon credits. If the activity would have occurred in a business-as-usual (BAU) context (without the incentive of credits), then the project is not considered additional. Many novel CDR projects utilize unproven or innovative technologies that have not yet become widely adopted. They are often a higher-risk investment or lack commercial alternatives. The carbon capture component of the project is inherently additional since emissions removal opportunities would not exist without the purchase of credits.

Though first-of-a-kind (FOAK) projects are additional because they are relatively unproven, they may result in the mainstreaming of novel CDR tech to the point that additionality becomes reduced over time. Some CO2 utilization projects are already commercially viable and therefore do not qualify as carbon offsets. Some transportation and geostorage operations are BAU activities as well. Separating the transport, utilization, or storage component from the capture activity allows the capture tech developer to retain the crediting capacity, while the transportation and geostorage components are an associated operational process.

What's Next – Part 2: Incentivizing safe & durable geostorage

To recap:

We can see that CDR is necessary to achieve Paris Agreement-aligned levels of emissions reductions.

Carbon capture, transportation, storage and usage are distinct but interrelated processes.

Utilization of emissions prevents the long-term geostorage of CO2.

Transportation of CO2 between capture sites and geostorage sites requires careful measurement of volumes and definition of ownership of emissions as well as access to subsurface reservoirs.

Geostorage is a complicated process that requires a higher level of due diligence than is already occurring.

Attempting geostorage within inappropriate reservoirs could compromise the reputational integrity of the entire CDR industry. Reservoir and infrastructure due diligence need to be prioritized to ensure safe and durable emissions removals. Prioritization of the best potential geostorage locations will also provide greater economies of scale for infrastructure development. If I learned anything from my time in petroleum exploration, it's that prioritizing the best reservoirs makes the most money.

Although various frameworks are evolving, definition of regulations, governing policies and incentives to promote safe and durable geostorage are currently very limited. It is possible to evaluate and verify subsurface sequestration capacity but presently, there is very little opportunity for profitability for those who know how to do so.

Part 2 introduces how defining a due diligence framework will enable profitability for the subsurface operator and will maximize our ability to permanently sequester emissions. We will also explore who are the players across the CDR ecosystem? How might they work together to strengthen CDR demand signals? And can petroleum companies transition from an operational model of hydrocarbon extraction to emissions sequestration? Click here to learn more:

How can we incentivize safe & durable geostorage? - Part 2

Welcome to Climate Drift - the place where we dive into climate solutions and help you find your role in the race to net zero.

If you are interested in collaborating, please email me at [email protected] or contact me on LinkedIn.

Join the Climate Drift Accelerator and accelerate your climate journey. We are selecting people for our next cohort now, and we're looking for talented individuals like you to make a real difference.

🚀 Apply today: Be part of the solution