Welcome to Climate Drift - the place where we dive into climate solutions and help you find your role in the race to net zero.

If you haven’t subscribed, join here:

Hey there 👋

Skander here.

If you’re wondering whether Climate Tech is teetering on the edge, let me assure you: it’s not dead. Far from it.

Let’s focus on the real problem: selling more climate stuff.

Because no matter how brilliant or breakthrough your climate solution is, it’s not going anywhere if you can’t line up big, steady buyers. Or, as the industry calls them, offtakers.

Today, we’re use the fascinating world of cement to see how offtake agreements can make or break a climate startup.

Cement might not sound glamorous, but it’s responsible for a 8% of global CO₂ emissions, so if we want to cut carbon fast, cement is exactly where we need to look.

But why aren’t we seeing more carbon-free cement offtake?

Buckle up: from messy stakeholder ecosystems to razor-thin commodity pricing, we’ll explore the “ABC” (Architecture, Buyers, and Commoditization) of why offtake is so tough.

🌊 Let’s dive in

🚀 Want to make an impact?

The 4th cohort of our accelerator launches beginning of March, and applications are still open (but spots are limited). If you’re ready to fight climate change, don’t wait:

But first, who is Tessa?

With a strong foundation in strategy development and execution, Tessa Peerless honed her expertise working with Fortune 500 companies as a consultant at Bain & Company and on the Strategy and Transformation teams at Worldpay/FIS. In 2023, she pivoted her career to focus on scaling emerging climate technologies in the built environment, combining her business acumen with her passion for sustainability.

Most recently, Tessa served as Chief of Staff at Material Evolution (Mevo), a UK-based low-carbon cement startup. During her time there, she gained invaluable insights into the challenges—and immense opportunities—of commercializing technologies aimed at reducing embodied carbon emissions. Now, she’s leveraging these lessons to drive decarbonization efforts in her home country of Canada, working on a new initiative to transform the built environment.

How do climate offtakes work?

This is another longer one. Read it fully by clicking on the headline 👆

What cement teaches us about selling climate solutions

What is the one thing The Empire State Building, your driveway and Climate Change have in common? Cement.

Cement is all around us - in the buildings we live, work and play in. Due to the sheer volume in which it is used, cement is currently responsible for ~8% of total global emissions (source).

The problem: cement related emissions are significantly off-track from emissions reduction targets to be in line with The Paris Agreement (source). And its difficulty in gaining offtake agreements - agreements which can be used to finance the growth of low-carbon cement companies - is one big challenge hindering the progress of cement decarbonization.

Green Cement and its Adoption Cycle

Why is the cement industry off-track from its emissions reduction targets?

The long answer: check out the piece I wrote about the cement industry and the context behind why it is such a big climate issue here:

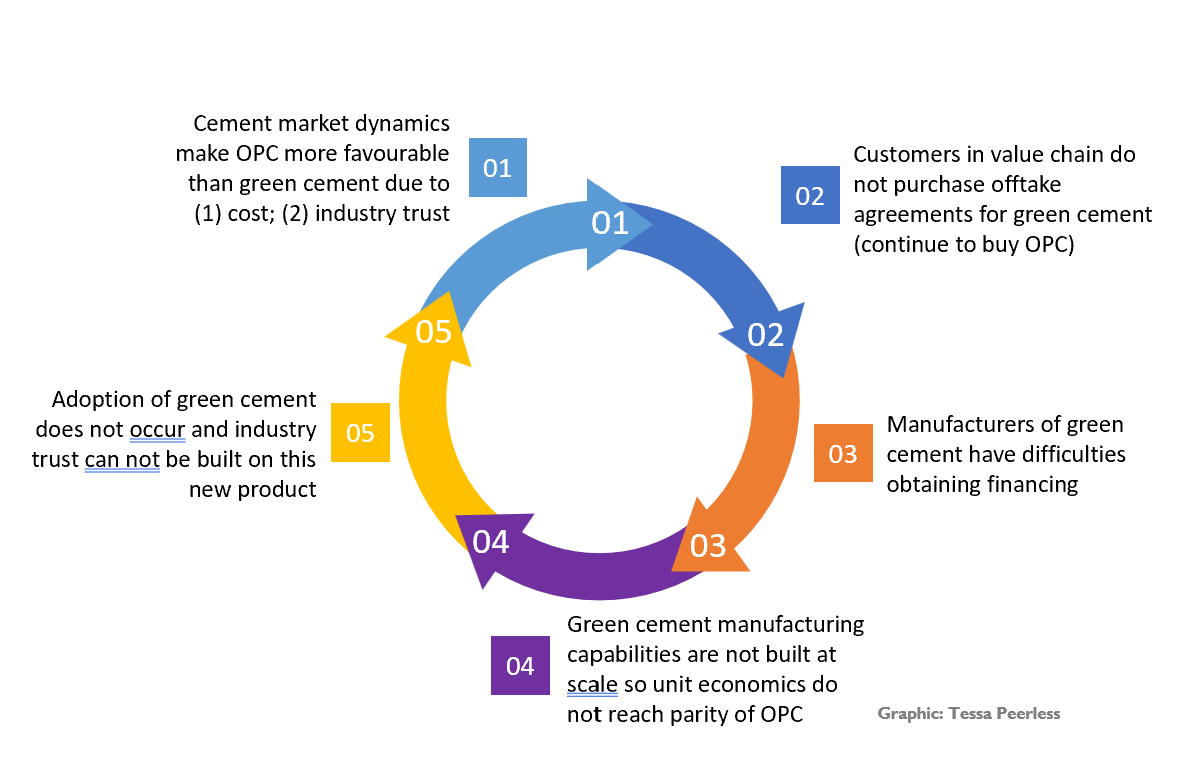

The shorter answer: as a start, we can focus on the industry dynamics inherent in the cement industry. The legacy industry’s commoditized and traditional nature, combined with its complex stakeholder ecosystem make it challenging for low-carbon cement companies to get customers who will take large volumes of product for long periods of time. And without customers, it is difficult for low-carbon cement companies to raise financing to build factories. This means that unit economics can not be scaled and therefore that cost parity to traditional cement products can not be achieved.

I’ve illustrated the low-carbon cement adoption conundrum in a cycle diagram:

To break the cycle and increase adoption of low-carbon cement, there are methods to influence and change the dynamics of each of the five steps in the cycle. The focus for this piece is understanding why cement market dynamics are detrimental to the adoption of low-carbon cement (step #1) and then focuses on creative approaches to enabling offtake agreements for low-carbon cement products (step #2).

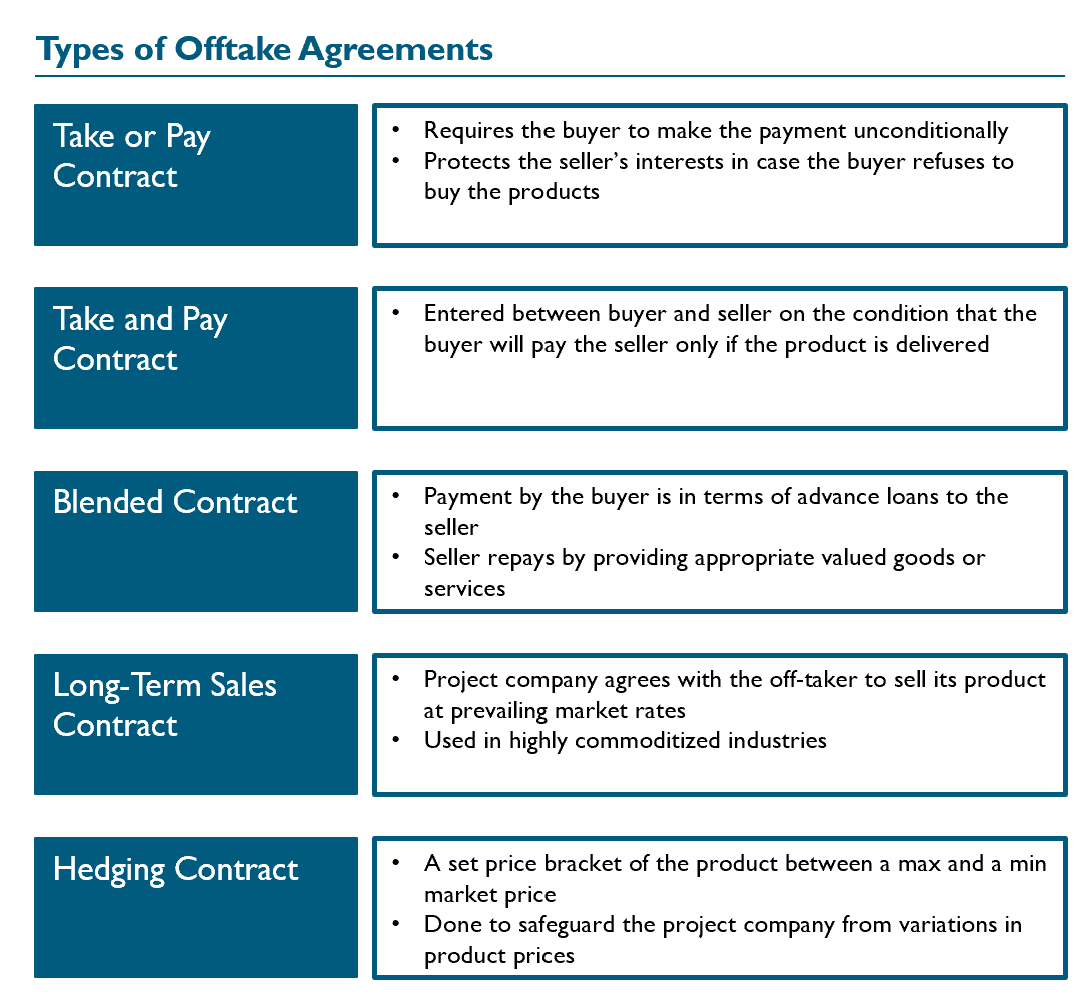

Offtake Agreements: A Tool to Reduce Commercial Risk

A climate techie’s favourite two-word phrase: offtake agreements. Offtake agreements are a tool which can be used (and have successfully been used: see the Rondo Case Study) to reduce commercial risk for climate technologies. An offtake agreement is a guaranteed revenue stream in the form of a customer who is willing to purchase the product at a set price. This tool reduces commercial risk by guaranteeing revenue following project completion. Offtake agreements come in many forms with various levels of risk on the side of either the buyer or the seller.

The structure which offtake agreements take can vary, with some examples illustrated below:

As illustrated in the cement adoption cycle above, a guaranteed revenue stream (often expected in the form of an offtake agreement) is often required for a hard tech company to gain financing from a bank (or to “become bankable”). And it isn’t hard to understand why. When the technology company has a guaranteed revenue stream, they also have a much higher probability of having funds to pay back their loan. So offtake agreements = financing potential.

In the most-bankable scenario, a provider would obtain multiple agreements from a diversified set of customers. To sweeten the deal even further, the ideal customers would be ‘blue-chip’: extremely reliable and valuable industry players who have a long history of financial stability. Together, these variety of blue-chip “offtakers” would ideally represent an offtake of the majority of the supply which will be produced by a particular project. I’m sure you can see how this scenario would lower a project’s commercial risk: it would essentially guarantee the project revenue and subsequent interest payments or equity returns.

But the cement market has some inherent challenges which make it challenging for them to obtain offtake agreements.

Cement Market Dynamics

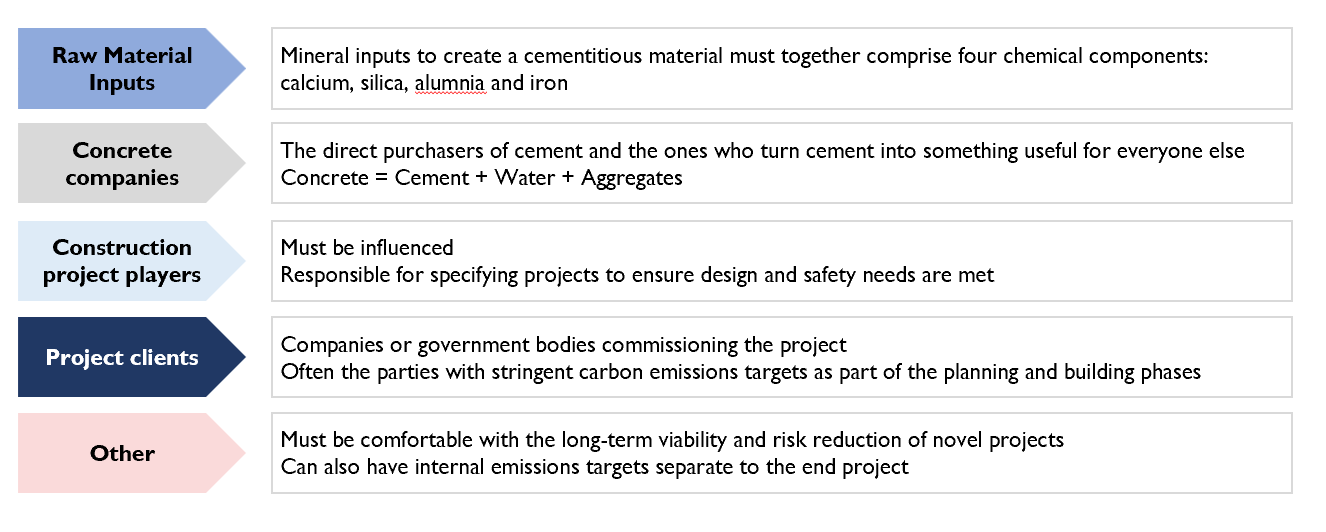

Cement producers are one stakeholder of the construction value chain, which includes many firms with unique expertise and contributions to the overall building project.

Cement Value Chain Flow

Every project which leverages cement begins with a purchaser, either private or government, who scopes the project and what they need it for (for example: a new road or office building).

To tangibly take the project from planning / scoping phase to a finished product, there are multiple steps of construction that need to take place. Architects & engineers must specify the project to develop a plan that is safe and aesthetically pleasing. Sub-contractors are hired to procure and install various bits of the project, one of which is typically a concrete sub-contractor. The main contractor and developer bring the project to life.

The cement manufacturer (the firm who in the situation of this piece is trying to raise funds to finance their manufacturing capabilities) is the black pentagon in the middle of the diagram above. They sell directly to concrete manufacturers, who (with some water and aggregates) turn cement into concrete, a product that is useful for the building project. The exact raw material inputs used to manufacture cement vary depending on the technology being used, but are a form of four chemical components: calcium, silica, alumina and iron.

There are some external players who can influence direct purchasers to use green cement. For example, Standards Accreditors can be convinced that a novel cement product or technology has the performance and safety required for it to be broadly used - and can adapt cement standards accordingly. Although not direct cement purchasers, this could influence others in the stakeholder ecosystem (for example, engineers and insurers) that a particular product is ready to be applied.

Although a simplified version of the value chain, it begins to demonstrate the complex stakeholder ecosystem.

Market Consolidation

There is significant consolidation between various players of the value chain. For example, with some concrete companies owning their cement supply and the raw material input source (e.g. limestone mines). This market consolidation makes it difficult for disruptors to reach parity on economies of scale, especially without owning their own value chain. The complex stakeholder ecosystem adds another barrier in that novel cement technology providers have a significant number of players to influence for their product to end up in a building project.

Commodity Market

Cement is widely considered to be a commodity product, with little to no distinction between the product being produced by various suppliers, in various locations or for various applications (source). The material produced and the process undergone to produce cement today has changed very little from the Original Portland Cement (OPC) which was first patented in early 1800s in England (source). So traditional cement manufacturers perfected the product long ago and can now solely focus on producing their product for the lowest possible cost to increase their margins.

The major implication of this for green cement suppliers is that prices of commodity products, like cement, are set standard in the industry, and are based on simple supply and demand dynamics. The price commanded is difficult to predict, as cement prices will fluctuate based on macro-economic drivers (for example, increased interest rates mean less building projects and less cement purchases required). And as concrete companies are in the business of purchasing a commodity product of cement that simply performs to a spec to get the job done, there is limited opportunity to create a ‘premium’ product. With a commodity dynamic in play, firms commercializing a green cement product have a difficult time commanding a Green Premium at scale for their product.

To recap commodity dynamic: low-carbon cement companies are mostly subject to commodity pricing which fluctuates based on the market and which they have limited future insight into. This dynamic is not ideal for bankability. This further increases the need for stable offtake agreements from blue-chip customers.

Levers to alter market dynamic and encourage demand

However, there are some levers which would alter the demand dynamic. On the demand side, there could be an increase in firms who purchase green cement, distinguishing green cement from the commodity market simply of ‘cement’. In the past few years, the demand side has been changing through a number of value chain participants. For one, the Global Cement and Concrete Association has committed to achieving net-zero concrete industry by 2050 (including detailed goals and deadlines to achieve this) (source). Property developers are seeing the shift coming as well with 47% of property developers globally stating that building decarbonization is fundamentally important to their business growth (HSBC). There has even been a rise in the number of private clients looking to decarbonize their building projects. For example, Microsoft stated that “the rise in [its] Scope 3 emissions primarily comes from the construction of more data centers and the associated embodied carbon in building materials” (source) and that is a step to Microsoft’s commitment to be carbon-negative by 2030 (source).

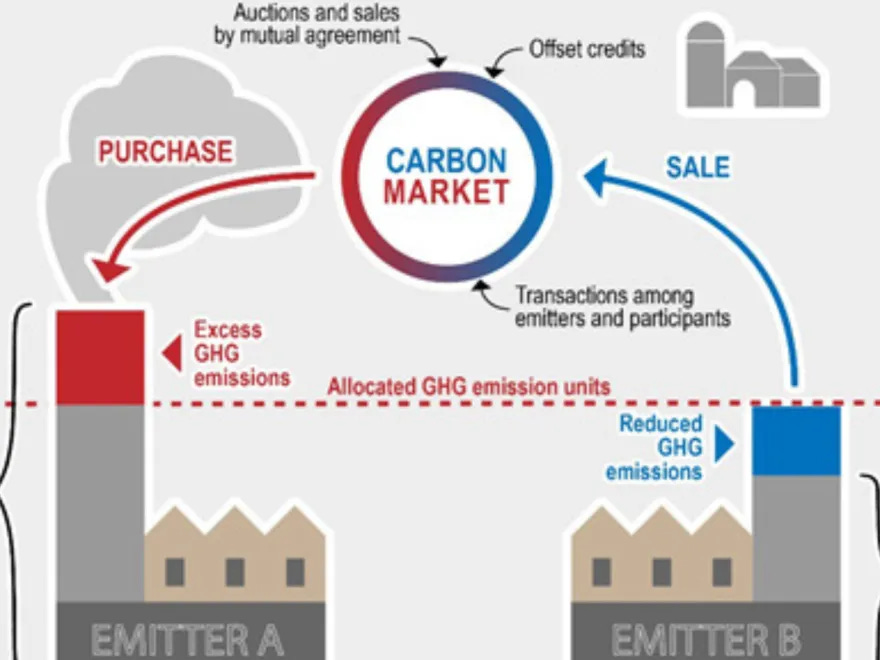

Cap + Trade

Pricing in the negative externalities associated with cement emissions can also influence this supply + demand dynamic. A cap + trade system, for example the EU ETS, is one way of doing this. The ETS, which is planned to become fully operational in 2027, will put a price on carbon for the hard to abate sectors, meaning that the cost of the cement commodity in the EU would increase, and to the purchaser would become the cost of cement + the cost of carbon that is emitted. Depending on the carbon price, this could provide an economic advantage for low-emissions cement providers when selling their products (source).

Book + Claim

Similarly, a book + claim system is a more flexible model which an influence the supply + demand of low-carbon products. There may be some buyers who wish to purchase low-carbon cement but are constrained from doing so. Some constraints could include limited supply of low-carbon materials in their location (cement is difficult and costly to transport long distances) or regulatory constraints limiting their options for low-carbon products (regulations are specifically based on the application of cement, so some applications are easier to de-carbonize than others). In addition to their purchase of cement (with its associated typically high level of emissions), these buyers could purchase a certificate which represent the emissions reductions from another tonne of cement that is sold. In return, a buyer who has less desire for low-carbon cement can use the product at a ‘discount’ which has been artificially created as a result of the certificate purchase from the aforementioned buyer. This stimulates an artificial demand for the low-carbon cement product as it flips around the supply + demand curve. (More about Book + Claim systems)

A Book + Claim system could add simplification to the complex stakeholder ecosystem by allowing organizations seeking decarbonization of their buildings to interact with low-carbon cement producers. The best part is, it could do so without needing to purchase the cement from them directly. Long term, a transparent monitoring and reporting system through a governing third-party body would be required to increase the legitimacy of such a system. RMI has recently released a report “Structuring Demand for Lower-Carbon Materials” which provides guidance on what a Book & Claim system would look like for low-carbon building materials.

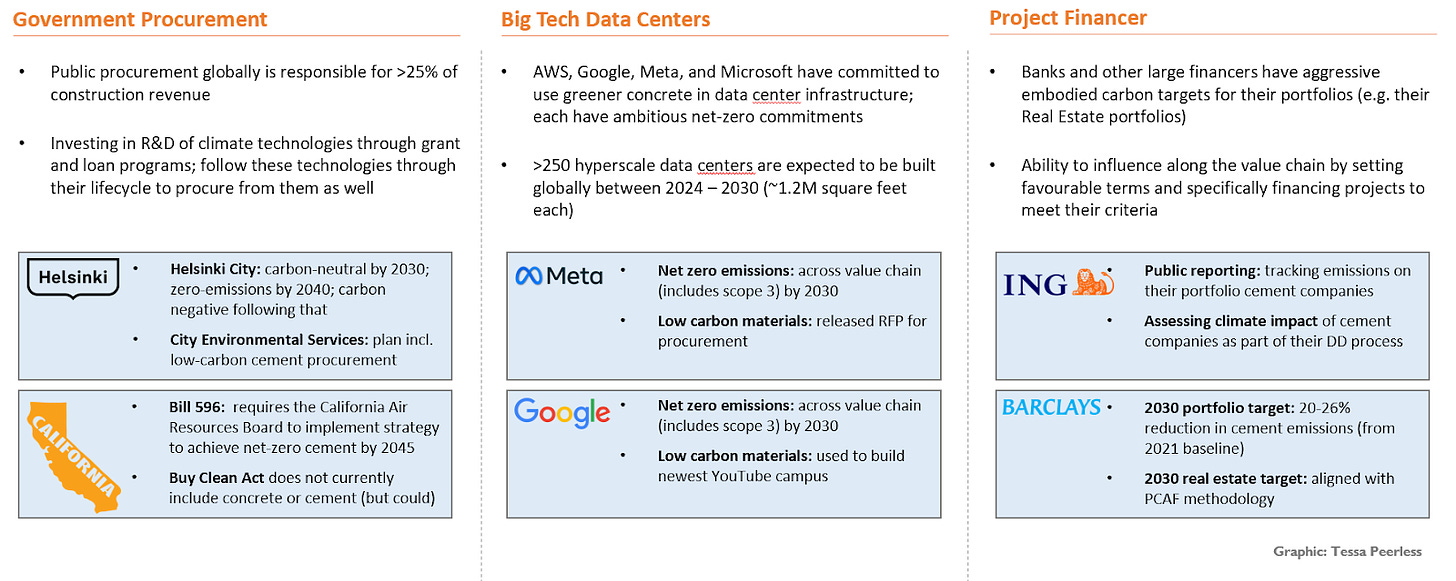

Personas: The Ideal Cement Offtakers

But while Cap + Trade and Book + Claim systems are fantastic in theory, they don’t exist at scale yet. Which brings us to an important question: which players might be the ‘first movers’ to voluntarily sign low-carbon cement offtakes? The good news is that there are a lot of fantastic opportunities. I’ve narrowed it to three which I see as being particularly promising:

Deep Dive: Governments as Offtakers

If I had to choose just one archetype to be the first movers in signing low-carbon cement offtakes, it would be governments. Let’s dig into why.

The Math

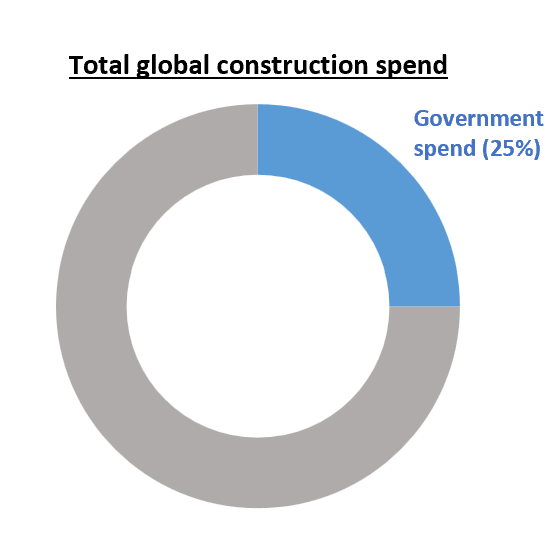

With cement market dynamics in mind and the understanding of early private-sector commitments to decarbonization, the next step is for public and government entities to make a meaningful, long-term commitment to low-carbon cement purchases.

Governments are among the top buyers of materials for major infrastructure projects. Public procurement is estimated to be responsible for 25% of global construction revenue (source).

When you’re looking at an industry which emits >4 gigatonnes of carbon emissions per annum, 25% of this has the ability to make a BIG impact. A quick back of the envelope would therefore indicate that if all global public cement procurement was to become net zero, that would reduce total global emissions by ~2% [8% emissions today x 25% reduction from public procurement = 2% emissions reduction from public procurement]. In the UK, where 30% of construction projects are undertaken by or on behalf of the public sector (source) and where cement emissions contributed 7.3 million tonnes of Co2 (1.5% of total CO2 emissions), if net-zero concrete was to be pursued by all government projects, that would equate to 2.1M tonne emissions reduction and almost half of one percent national emission reduction.

A Ripple Effect

More important than just these direct figures would be the potential for a government ripple effect to accelerate low-carbon cement technologies in two exciting ways.

The first, is revenue stability. These agreements could provide revenue stability for low-carbon cement companies to finance their FOAK and NOAK facilities, de-risking future offtake agreements from an operational and technological standpoint and getting these companies through the Valley of Death. It could also help low-carbon cement technologies invest further in R&D and operational efficiencies to ultimately make the cement cheaper and of better performance than OPC.

A great example of this is in the solar industry. From 1974 - 1981, the US government (in response to the Arab Oil Embargo) implemented programs to accelerate the development and subsequent cost reduction of the technology. A public procurement program known as the Block Buy program sustained early demand for the technology. This demand, in addition to federal funding and the public signal to the private sector that the technology was ready to be commercialized, was a crucial driver to the success of the technology today (source).

The second, is regulations. Government bodies could work to modify existing cement and concrete regulations to be performance-based rather than material-based; leveraging the case studies from their projects as the backbone. For the private sector, these initial projects and ensuing regulatory changes could mark an important signal that low-carbon products are safe and effective to use in building and infrastructure projects.

The great news is, some government entities have already made public commitments to their low-carbon building procurement. Let’s look at two examples:

Case Study A: The City of Helsinki's Roadmap for the Circular and Sharing Economy

Helsinki has publicly stated an overarching goal for the city to be carbon-neutral by 2030, zero emissions by 2040 and carbon negative following that (source; source). To meet this commitment, the city has publicly stated their goals and targets, including two that relate directly to cement emissions: “Discontinuing the use of lime cement as binder in soil improvement” and “Low-emission concrete in infrastructure projects” (source). Longer term, the city has also set a goal that there will be ‘circular economy criteria’ for all public procurements by 2050.

As part of this, the City’s Environmental Services has outlined actions that the city will take toward a circular economy. Two such actions which relate to low-emissions cement procurement. First is an Infrastructural Construction Action: “Studying the opportunities for reducing the amount of concrete and using low-emission concrete or substitutes for concrete in the City’s infrastructure. Similarly, promoting the use of binding agents made of recycled materials in deep stabilization, which will reduce the use of high-emission cement and burnt lime as binding agents.”. Second, is a Building Construction Action: “Studying the opportunities for reducing the amount of concrete and using low-emission concrete or substitutes for concrete in the City’s building construction.”

Case Study B: California’s Bill 596 carbon-neutral cement requirement by 2045

Bill 596, passed in 2021, requires the California Air Resources Board to develop and implement a comprehensive strategy to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions associated with cement used within California as soon as possible, but no later than 2045, and to establish interim targets for reducing cement’s greenhouse gas intensity (source). While this is a great first step, a next one would be for California to add cement as one of the materials of California’s Buy Clean Act, which sets limits on carbon emissions from particular materials (currently structural steel, concrete reinforcing steel, flat glass and mineral wool board insulation) when being used in public works projects (source). Even if this was to be applied only to roads and sidewalks in the state (which is also the world’s fifth largest economy), that comprises 40% of the concrete currently used in the state (source).

To Conclude

Offtakes are an important step in wide adoption of green cement. Although there are many challenges that exist in gaining offtakes for low-carbon cement, there are many potential first-movers to offtake low-carbon cement. And I’m confident that we are on a path to meaningfully and dramatically reducing the commercial risk of low-carbon cement.

Interested in learning more or chatting about industrial decarbonization? Connect with me!

More resources on cement offtakes: