New Material matters

How are advancements in material science driving the shift towards a circular economy?

Welcome to Climate Drift - the place where we explain climate solutions and how to find your role in the race to net zero.

If you haven’t subscribed, join here:

Hi there! 👋

Skander here.

We're moving forward with our Climate Drift Fellows series, exploring various fields and ways to address climate issues.

Today Nghi Lam is diving into innovations in material science for a circular economy.

Nghi has spent a decade as the go-to technical fixer in business systems, crafting solutions for internal processes. With foundational roles in Business Systems at companies like Docusign, Cisco Meraki, and Amplitude, Nghi has engineered solutions across all business functions.

Now, pivoting towards environmental impact, Nghi seeks to leverage this expertise to solve problems in climate.

Interested in joining the climate fight and working on the challenges faced by climate companies? Apply to our next cohort here:

Let’s dive in. 🌊

What innovations in material science are facilitating the transition to a circular economy?

“Ew, I touched the bay!” a passerby shouted to their friend as I landed my kayak on Encinal beach of Alameda, California. I regularly paddle here, so I took some offense, but I also understood the sentiment. It wasn’t a particularly bad day in terms of visible waste, but water has a way of exposing pollutants based on its own clarity (or lack thereof).

Living in the Bay Area, the sight of murky water and beached trash is normal. Such is the case with cities and countries with a coastline, water exposes the inadequacies of waste management systems and highlights the prevalence of global waste. How do we best mitigate waste in a consumer-driven, material world?

Circular Economy

The circular economy is a framework for thinking about how consumer products are designed, produced, and reach their end of life such that materials are never wasted. Instead, they are in continuous circulation. As you might surmise, the circular economy starkly contrasts traditional manufacturing which moves linearly – consuming raw materials to create products that are used and then disposed of in landfills.

As the impact of climate change looms overhead, there must be a global effort to transition to circular economy practices to reduce worldwide waste. This is a massive endeavor given our existing manufacturing systems which undoubtedly calls for major changes to the inputs of these systems. Specifically, this briefing focuses on advancements in materials science – an interdisciplinary study of existing materials’ properties and behaviors that enable the development of new materials. In the circular economy, these innovations are guided by the following principles:

Reduce waste

Conserve resources

Promote sustainable consumption and production practices

Regenerate nature

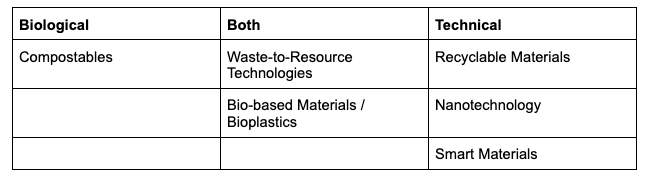

The implementation of these principles within materials science fall into categories that span material types and technical processes. While these groupings can be difficult to conceptualize, they are worth understanding holistically to be able to strategize the transition to a more circular economy. Therefore, I have attempted to delineate these innovations under the following groupings:

Materials Science Innovations in a Circular Economy

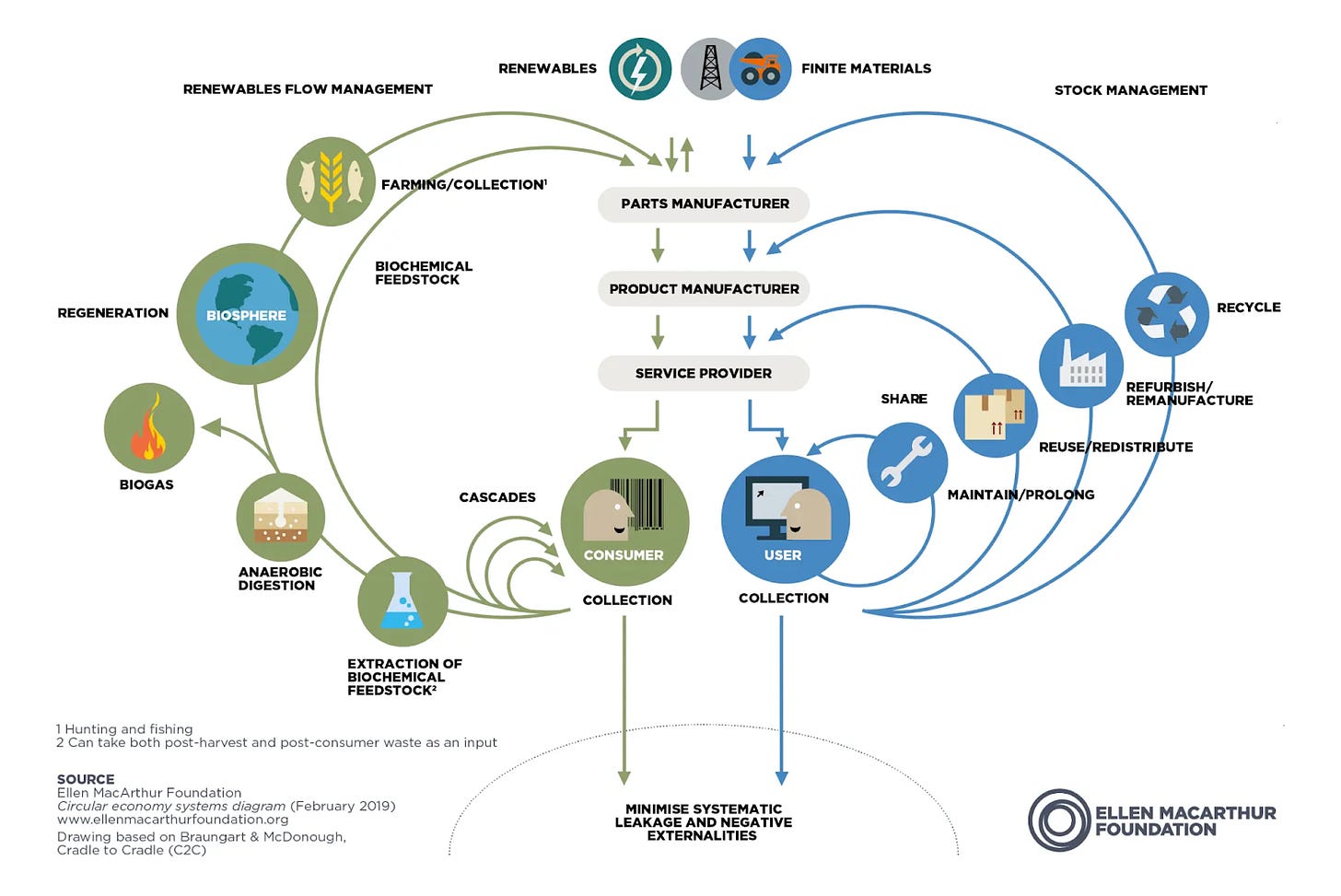

The circular economy systems diagram by the Ellen Macarthur Foundation divides circularity into two realms: biological and technical. While certain materials can move through both contexts, this divider distinguishes different processes that a material undergoes within the circular economy.

Biological

processes that “return nutrients to the soil and help regenerate nature”

Compostable / Biodegradable vs. Biodegradable

Adopting compostable materials in manufacturing is a step towards reducing waste in the environment while restoring nature too. A single-use product made of compostable materials can decompose into harmless byproducts in a composting facility or in nature. All compostable materials are inherently biodegradable, but the term “biodegradable” has become contentious in recent years. This is because there are standards and time constraints set for compostability; whereas, biodegradability is vague without specifics around timing or environment needed for decomposition.

Regardless, waste management of compostable materials (all materials, really) is important. If compostable materials are incorrectly disposed of in landfills, it would contradict their replacement of other materials while potentially contributing to methane emissions too.

Example:

ECOVATIVE (United States) grows packaging out of hemp hurd and mycelium (mushrooms). As of 2019, ~31% of plastic production was for product packaging. Alternative, compostable materials for packaging is a major opportunity for reducing plastic waste.

Biological → Technical

Waste-to-Resource Technologies

Waste-to-resource technologies reduce our existing levels of waste by giving new life to industrial byproducts, converting waste to bio-based and / or compostable materials. Looking into these technologies is hopeful, as there are several examples of entrepreneurs who have been able to transform local sources of waste into materials, products, and jobs for members of their community.

Additionally, a subset of these WtR technologies goes one layer (atmospheric? 😉) above managing physical waste by capturing and using greenhouse gasses to produce manufacturing materials!

Examples:

CHUK (India) repurposes sugarcane waste (“bagasse”) to create tableware.

LIFEPACK (Columbia) repurposes pineapple crowns to make plates and packaging. When composted, the material contains embedded seeds that can sprout in the natural environment.

Mango Materials (US) partners with methane-producing facilities to capture and feed methane to ancient bacteria (methanotrophs). These methanotrophs then create high quality materials which Mango Materials turns into YOPP PHA plastics.

Carbonaide (Finland) captures carbon dioxide and uses it in place of cement in the concrete-making process, one of the most carbon emitting processes in manufacturing. This process creates concrete with fewer emissions while also serving as a carbon sink for captured CO₂.

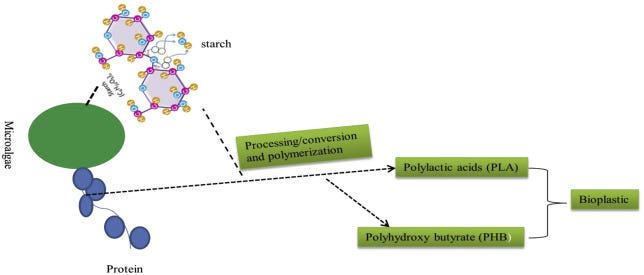

Bio-based Materials / Bioplastics

Not to be confused with “biodegradable”, “bio-based” refers to the source of the material used to create it. Identifying a material as “bio-based” is meant to distinguish it from traditional, fossil-based materials – highlighting it as a sustainable alternative that can be created from renewable biomass sources like plants, animals, marine, and forestry materials.

However, because of the variety of renewable source material, developing bioplastics can be quite challenging. Creating plastic involves a chemical process that converts simpler, “precursor” molecules to a chain of polymers. Traditionally, these precursor molecules are derived from petroleum whose conversion pathway is well understood. The challenge of creating bio-based plastics is rooted in discovering alternative conversion methods for the various “precursors” that come from renewable biomass sources.

Transitioning to bioplastics could decrease our dependence on fossil fuels AND chip away at worldwide waste with a few caveats:

There is understandable concern in pivoting to bioplastics if net new crops are planted to fuel the bioplastic industry. When exploring this option, there should be a concerted effort to leverage existing biomass sources like waste rather than setting up new crops to feed bioplastics instead of people.

As established above, bioplastics are more diverse than fossil-based plastics. This is problematic for recycling centers when the materials are incorrectly mixed together. Furthermore, not all bioplastics are biodegradable, and even the biodegradable ones require special conditions to fully degrade.

With these potential pitfalls, bioplastics are a risky investment that require significant attention to product application and waste management to prevent them from becoming a new waste stream. They can be effective in the right application – like a bioplastic that is home compostable would do well in a use case where it touches the food item and can be composted with it. For example, a compostable bioplastic replacing the material used to bag tea leaves. Typically, plastic that is contaminated by food doesn’t get recycled, so this type of replacement would help reduce plastic waste.

Examples:

BIOFASE (Mexico) recovers avocado pit agrowaste to create a biopolymer which they then use to produce cutlery.

The diagram below depicts the creation of bioplastics from microalgae:

Technical

focused on how products are more effectively used

Recyclable Materials

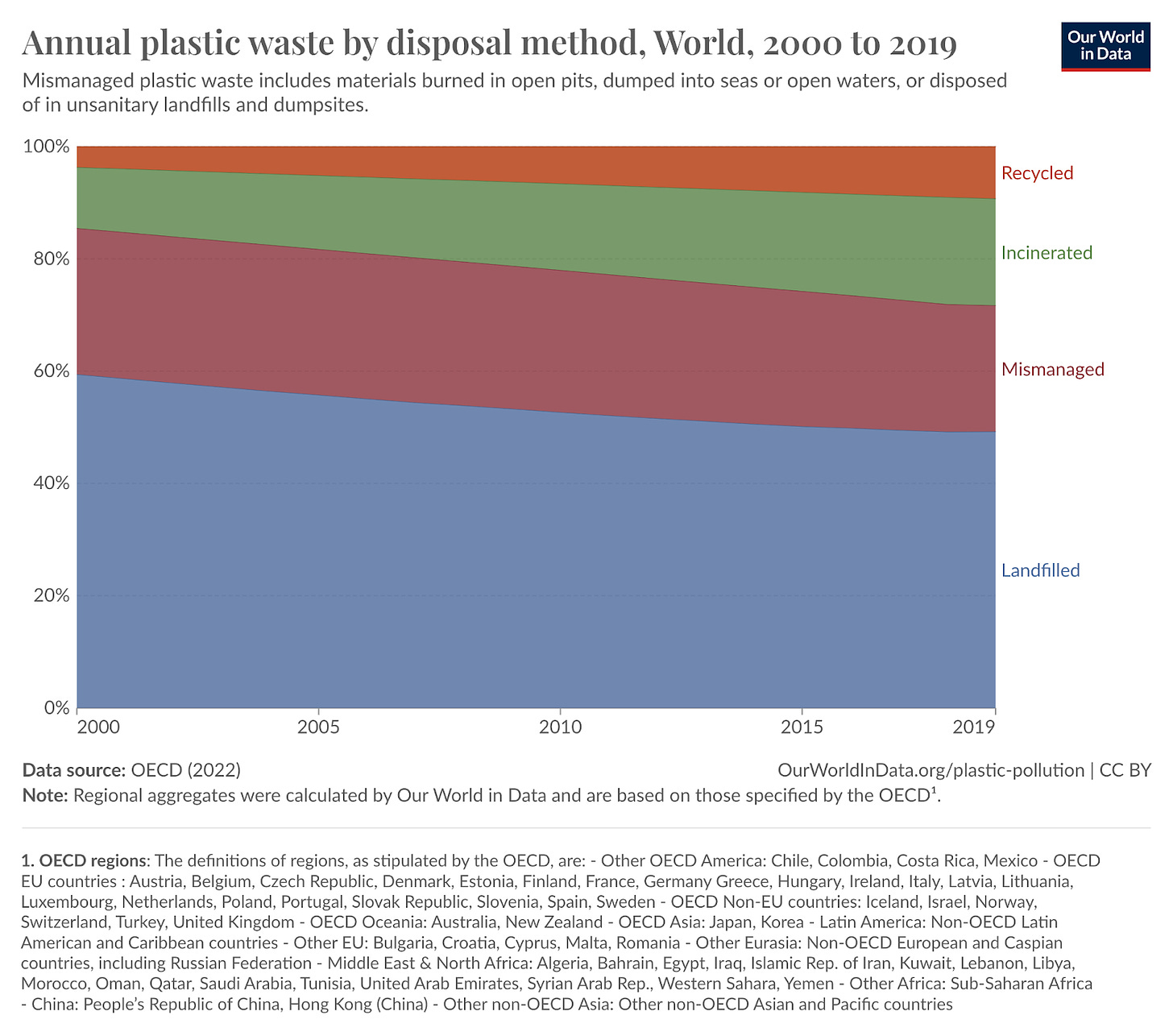

The technical side of the circular economy diagram relies heavily on recycling which is a process that allows us to conserve resources by more efficiently using materials. Recyclable materials can be reused in manufacturing after undergoing a recycling process, tailored for that particular material. Like all materials, how the product and material are managed at end of life is critical because only a staggering 9% of recyclable plastics are actually recycled in our current ecosystem.

While our most ubiquitous example of recyclable material is plastic, this is a growing category composed of other materials too. Advancements in recycling technology and in material properties (via materials science research) both affect recyclability of existing materials.

Recyclable plastics like polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and high-density polyethylene (HDPE) are widely used in packaging for beverages, personal care products, and household items.

Engineered wood products are made from wood fibers or residues bonded with adhesives. Some examples are plywood, oriented strand board (OSB), and laminated veneer lumber (LVL) all of which can be used in place of solid wood.

Recycled rubber is a result of innovative recycling technology that can break down tires into their material components, particularly rubber. Recycling rubber reduces the environmental impact of tire disposal and conserves valuable resources by giving new life to discarded materials.

Recycled textile is also a new category of material enabled by advances in textile recycling. Sulzer, a prevalent textile recycler partnered with H&M, describes a recycling process that separates existing textiles into 100% PET resin as well as cellulosic fiber. This fiber can then be respun and used to produce new garments.

Recycled concrete aggregates come from construction and demolition waste that undergo a simple recycling process: breaking down existing concrete into specific sizes while removing contaminants. Recycling concrete helps reduce the demand for virgin materials and diverts waste from landfills.

Nanotechnology

Nanotechnology is the manipulation of matter (1 to 100 nanometers) in partnership with existing materials to enhance specific properties of that material, such as strength, durability, and conductivity. This partnership creates materials with longer lifespans, greater reusability, and can increase the material’s efficacy as a product. Because of its additive nature, nanotechnology already appears in various industries as a simple enhancer to existing materials and products.

In the food world, silver nanoparticles are added to packaging materials because of their antimicrobial properties to extend a food item’s shelf life. The same nanoparticle can be paired with different materials to serve a similar function. Like in athletic clothing, companies have begun adding nanosilver to textiles to prevent odors from exercise.

Because nanotechnology is still rather nascent, responsible adoption should include studies on how certain nanoparticles affect living organisms and the environment in higher concentrations. After all, the theme with these innovations is to consider the entire lifecycle of existing and new materials.

Example:

NFINITE enhances the physical properties of compostable packaging material with layers of nanoparticles. This allows for compostable packaging that performs like traditional, plastic packaging when it's encasing food and can degrade easily afterward.

Smart Materials

Dynamic, superhero-like materials, smart materials can adapt to their environment and change properties as a response to stimuli like light, heat, electricity, and humidity. Responsiveness to the environment is promising because one product can potentially replace multiple, single-feature products. For example, Iberdrola posited that smart materials can create a multi-functional jacket with valves that open and close based on temperature and humidity, allowing you to comfortably wear the same jacket in various conditions.

Smart materials allow us to reduce waste by combining many properties into fewer materials, and types of smart materials that can continuously be re-shaped are infinitely recyclable too. The idea of smart materials in the circular economy is definitely compelling, but more research is needed to understand the emerging types of smart materials in order for them to be a viable replacement for existing materials today.

Examples:

Graphene

Shape Memory Materials

Self-healing Materials

What’s Next — Guideposts for Transitioning to Circular Practices

Moving to a circular economy is a challenging transition that requires major change management. It’s frightening but also a place of opportunity. From doing this initial research, I offer the following guideposts for those considering the transition:

Reduce production. The best way to reduce waste is to not create it.

Wherever possible, re-invest in nature through compostables. Reduce waste through collection and transformation of waste into compostable materials via Waste-to-Resource technologies. Consider nanotechnology to enhance physical properties of compostable materials by use case.

For existing materials and products that are considered “recyclable material”, create collection methods for used stock AND optimize the recycling process for each type of material. Modify product lines to adopt these recycled materials, but also consider where new substitutes can be applied like nanotechnology-enhanced materials or smart materials.

Explore nanotechnology to extend the lifespan and re-usability of recyclable materials.

For new and existing products, build processes to manage products at their end of life.

Within the Climate Drift Career Accelerator program, Johann Boedecker of Pentatonic spoke to us during our circular economy week. He described a plausible vision for the future where you could wear a different outfit every day, and instead of being washed, it would rebuild itself. It’s a future where products can be formed in-demand, last for as long as they’re needed, and easily break down into building blocks for the next use case.

This initial deep dive was to understand a baseline of the current material types we are working with that could propel us to that vision, but it seems I’ve only scratched the surface. Johann also mentioned something that resonates with the kayaker in me — that we should look to nature as a reference for some of these material breakdown processes, as a sort of “biomimicry”. Nature already manages to efficiently produce and decompose materials in volumes we cannot fathom, which goes to show why so many of us like to spend time being in awe of it.

Follow-up Avenues to Pursue

Dumpster dive into waste management across regions to better understand system leakages

Recycling technologies – why only 9%?

Break down nanotechnology further – consider self-assembly

Understand waste breakdown by industry. Where is the low-hanging fruit?