Welcome to Climate Drift - the place where we dive into climate solutions and help you find your role in the race to net zero.

If you haven’t subscribed, join here:

Hi there!

Skander, here.

Batteries are becoming a key player in the energy transition, with demand growing exponentially as various sectors adopt battery technology. This domino effect is driving down global fossil fuel demand, as highlighted in RMI’s recent report.

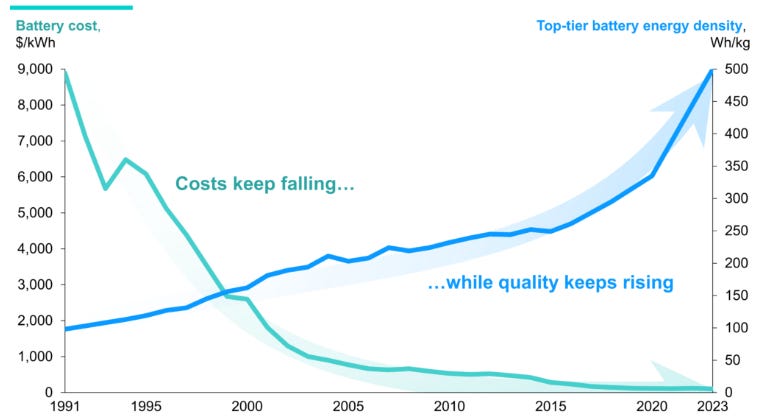

From consumer electronics to electric vehicles, batteries are climbing S-curves of adoption, with sales doubling every two to three years. Battery prices have dropped 99% over the past 30 years, while energy density has improved fivefold.

This has opened doors for batteries to be used in more applications, further accelerating their growth. The drivers of this change—falling costs, increasing policy support, and rising competition between economic blocs—will only strengthen in the coming years.

Explore the evolving landscape of battery technologies, from lithium-ion dominance to the rise of LFP and sodium-ion batteries. Climate Drifter Harrison Tramposch dives deep into applications, investment needs, and the importance of onshoring for a sustainable future. Ready to find out which batteries are leading the charge?

🌊 Let’s dive in

🚀 If you want to make a difference and bring your talent into climate:

Apply to our next cohort and join the Climate Drift Accelerator.

Interviews and admissions are happening right now.

But first: Who is Harrison?

Harrison Tramposch is currently a sustainability professional within the financial industry. Most recently, he served as a Business Analyst on Nasdaq's ESG & Climate Advisory team. He streamlined operations for a 20+ member team, supported business development and new solutions, and helped provide ESG strategy recommendations to companies across various sectors.

Harrison is driven by a passion to work on projects that mitigate the most severe effects of climate change alongside like-minded individuals. This might involve helping companies identify the most material issues for their business or conducting research into specific climate-related verticals to understand emerging trends. His recently launched Substack explores themes critical to achieving a net-zero transition by 2050.

Powering the Future

(Click 👆 to read the full thing online)

Intro: State of batteries

How long do you think batteries have been around for? Let’s take a look. Alessandro Volta is credited for inventing the Voltaic Pile. The Voltaic Pile was constructed with zinc and copper discs which produced an electric current. The voltaic pile receives credit for being the first type of battery.

Fast-forward to now, batteries have developed tremendously and are used across many types of appliances and machinery. Batteries are playing a critical role in helping decarbonize transportation, storing energy from renewable energy sources, and becoming prominent enough to push investment in a national battery recycling program and critical material recovery.

This post is divided into two parts. Part one includes a battery primer of the most commonly used batteries and their use cases. Part two includes information about recycling batteries, the global battery supply chain and how improper recycling fuels a growing e-waste problem. Lastly, the article ends with my bull, bear, and base case scenarios for the future.

Part 1: Battery Primer & Use Cases

Types of Batteries

Lithium-ion Batteries

Lithium-ion batteries are the most widely used battery type on the market. Their growing popularity is largely due to the increase in EV sales year over year and continuous advancements in battery technology. These factors make lithium-ion batteries a highly convenient choice. Exhibit 5 below illustrates a positive reinforcement loop essential for scaling lithium-ion batteries. The depicted economies of scale can serve as a model for other battery development or climate solutions for the energy transition (all else equal).

The double line graph spanning decades demonstrates the drastic drop in battery cost from 1991 to 2000 and a smoother decline from 2000 to the present day. During those same years, the battery energy density climbs steadily up and to the right.

No other battery has had a tremendous reduction in battery cost and experienced consistent improvement in energy density. If different batteries have similar success in research and development, a diverse battery rotation can occur and relieve the burden in sourcing critical minerals in an intricate global battery supply chain. Further development in different battery chemistries is required given different demands in final use-case products.

Inside a Battery Cell

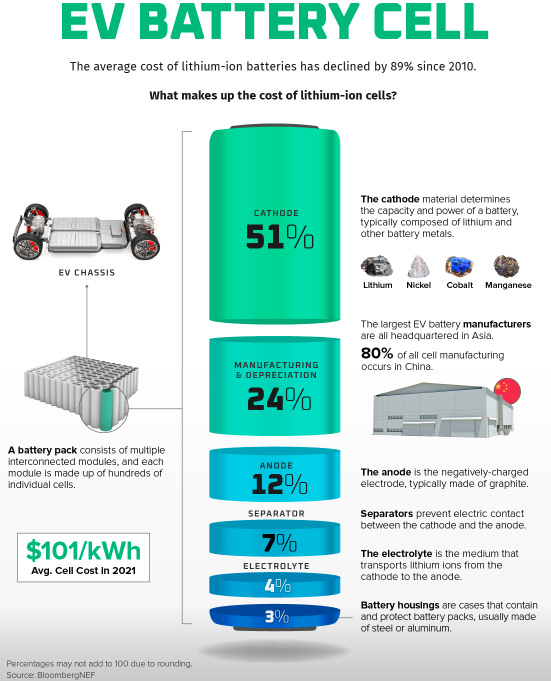

The lithium-ion battery contains four parts: a cathode, an anode, an electrolyte, and a separator.

Both the cathode and anode store lithium-ions while the electrolyte helps move the lithium-ion from the cathode to the anode during the charging and discharging mode. The separator found in the middle prevents short circuiting (aka the battery going on fire).

Lithium-iron phosphate (LFP) Batteries

Lithium-ion phosphate batteries are growing to become the battery of choice for energy storage. LFPs are positioned well to become energy storage’s go-to battery because of their lower costs, higher cycle lives, and greater thermal stability. These characteristics are more important given the function of energy storage compared to powering an electric vehicle. For example, energy storage needs to hold solar energy and be on standby (minutes to hours or even days) to power different systems.

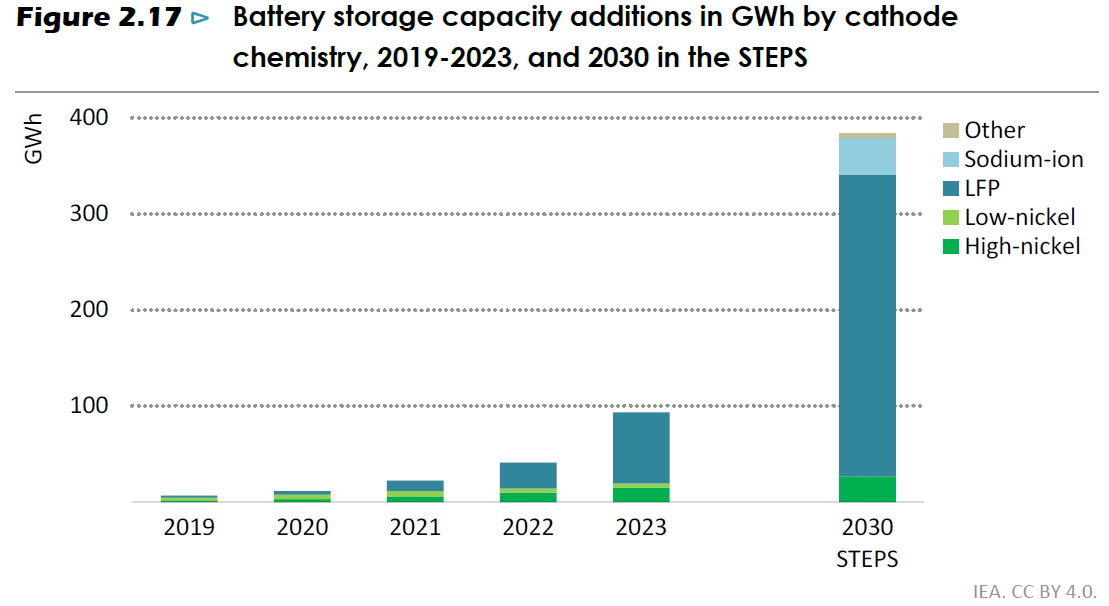

Masen, the Moroccan Sustainable Energy Agency, is a great example showcasing how important energy storage durability is to withstand tough environments. Scaling energy storage to function adequately in difficult environments is critical to achieve a widespread energy transition. In the past 3 years, the LFP battery share in energy storage capacity increased by 80%. Under IEA’s 2030 STEPS scenario, battery storage using LFP batteries is forecasted to have exponentially growth in GWh capacity and be a leader by 2030. The 2030 STEPS scenario forecasts sodium-ion to grow as well, well talk about that next.

Sodium-ion Batteries

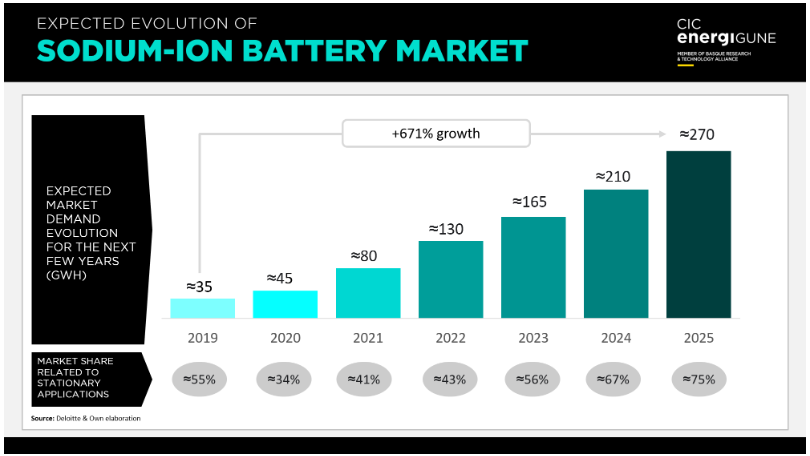

Sodium-ion batteries are advantageous in battery construction because sodium-ion batteries need fewer, less expensive materials. Sodium-ion batteries gathered attention in 2023 when Hina produced the first Sodium-ion powered EV. Finding batteries that rely on less expensive and less sought-after materials is highly advantageous, serving as a much-needed short-term solution to scale other batteries for transportation and battery storage use.

An important distinction in battery chemistry is sodium-ion batteries have a lower energy density compared to lithium-iron phosphate batteries. Both are forecasted to grow in battery storage applications because both sodium-ion and lithium-iron phosphate batteries have greater ability to tolerate heat stress and lower material costs. Taking into account how the research and development for lithium-ion batteries has scaled consistently, the same could be possible with sodium-ion batteries.

Battery applications

Application 1: EVs

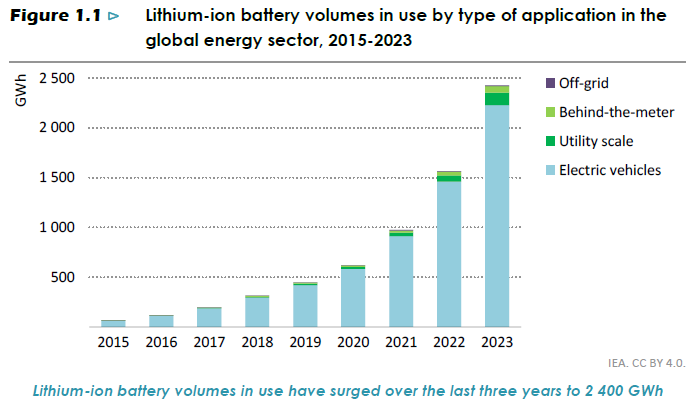

As mentioned, lithium-ion batteries are commonly used in many electric vehicles. Figure 1.1 demonstrates the heavy volume of lithium-ion batteries going into electric vehicles and the yearly increase in GWh capacity to power more EVs.

One important difference is the use case for EVs and energy storage have different requirements. Cars need to be durable in all types of road conditions and handle car demands in accelerating, braking, and maneuvering. Increasing energy density maximizes driving range while minimizing battery weight, improving overall vehicle performance. High power output is critical for EVs to accelerate and function like a normal ICE car. Advancements in battery research and design are crucial because electric vehicles (EVs) typically weigh more than internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles. Developing lighter, more compact batteries can significantly enhance overall EV performance.

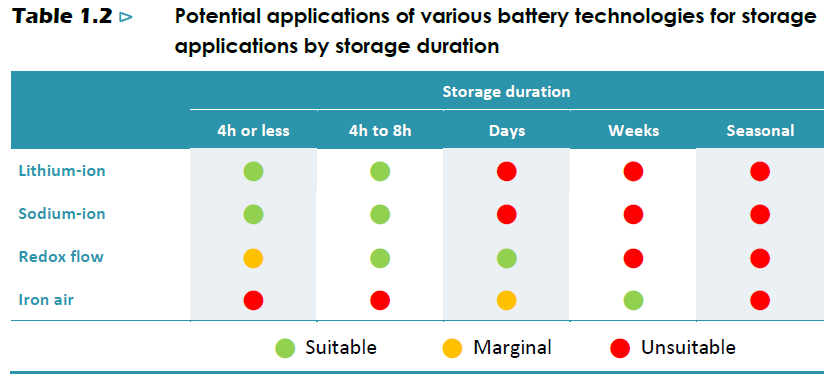

Application 2: Battery Energy Storage

Battery energy storage systems prioritize high life cycle, reliability, and energy capacity. Unlike EVs, battery energy storage systems do not require very high energy density because battery storage is stationary. If more energy density is needed, battery energy storage systems can be interconnected. For example, a battery storage system that connects to a grid would require higher power density to provide immediate energy in case of an emergency, such as a power outage. Conversely, long-term energy storage does not require high power, as its primary use is to store energy for extended time periods. Battery energy storage also needs to be highly durable across various environments, such as Masen in Morocco. Table 1.2 shows the storage duration time across four types of batteries used in energy storage.

The different application requirements have opened opportunities for other battery innovations because lithium-ion batteries (as shown in the table above) do well in short-duration intervals equal to or less than eight hours. Comparatively, lithium-iron phosphate (LFP) batteries have been growing in popularity for energy storage due to their safety, longevity, and durability. Redox flow batteries use liquid electrolytes that flow through electrochemical cells, making them highly scalable and ideal for energy storage applications with long-duration capacity. Iron-air batteries rely on oxidation and reduction of iron to store and release energy. Iron air batteries offer a low-cost, long duration energy storage solution by using abundant materials like air and iron.

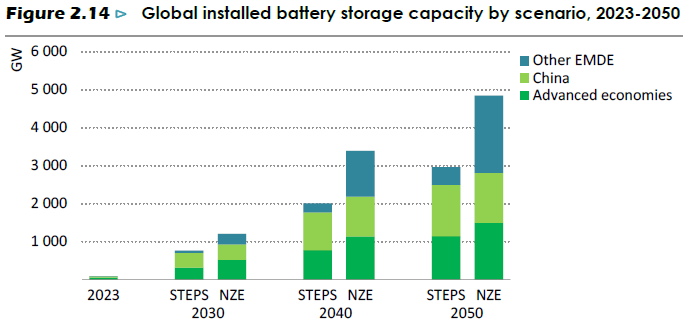

In both the STEPS and NZE scenarios below, battery storage is expected to grow significantly each decade across China, advanced economies, and other emerging and developing regions. The forecasted increase in battery storage installation factors in anticipated growth in investment, declining project costs, and the rising demand for power system flexibility (such as battery storage integrated with grids).

Part 2: Recycling, the Battery Supply Chain, & next steps

Intro

As electric vehicles become increasingly common and the United States aims to achieve goals such as having 50% of new car sales be electric by 2030, a supporting market for second-use batteries is inevitable. This market can provide a short-term solution to alleviate reliance on the global battery supply chain. A long-term goal can be developing a localized battery supply chain within the Western Hemisphere.

This McKinsey illustration depicts the life cycle of an EV battery, from its initial production to how used battery packs are sorted for their next phase. Once a battery is no longer suitable for electric vehicle use, it is segmented into three main pathways: repurposing for secondary use, recycling for valuable materials, or disposal.

Usable battery packs for secondary life go to a battery refurbishing company like ReJoule, RePurpose Energy, or Spires New Technology. These companies are focused on assessing the battery power and determining the best use case for a second life. Other batteries unable to be substituted for second use are perfect for companies like Li-Cycle or Redwood Materials. These two companies take batteries, break down the batteries to obtain the critical minerals, and refine the critical minerals for resale in a localized close loop supply chain.

Understanding the EV Battery Refurbishing Process

This Sand Report evaluated the technical and economic feasibility for second use batteries repurposed for stationary applications. The findings in the report are positive, as the commercialization of used and reconditioned batteries is already underway. These reconditioned EV batteries have enough energy to power stationary applications given the power demand is less on average compared to powering an electric car. Larger stationary applications can have EV batteries joined together in a big, makeshift battery pack. For the leftover batteries that are no longer suitable even for these less demanding secondary applications, recycling becomes crucial. The process of breaking down these batteries to recover essential minerals, such as lithium, cobalt, and nickel, is vital to reducing resource extraction and retaining batteries in a circular model. This not only minimizes environmental impact but also helps meet the growing demand for these critical minerals.

Additionally, the figure in the report below summarizes the steps required to refurbish EV batteries for second-hand usage. This multi-step process is intricate and needs to be followed diligently to ensure second-hand batteries function properly. The process of refurbishing EV batteries for stationary applications highlights the bespoke configuration and precise attention needed because all batteries are made differently due to a lack of standardization. Larger systems, such as combining over 100 full EV packs, can complicate shipping due to the new battery pack size. Slightly smaller battery packs are preferable because they are easier to transport. The time-intensive and non-standardized process of refurbishing these packs can increase both installation costs and labor demands.

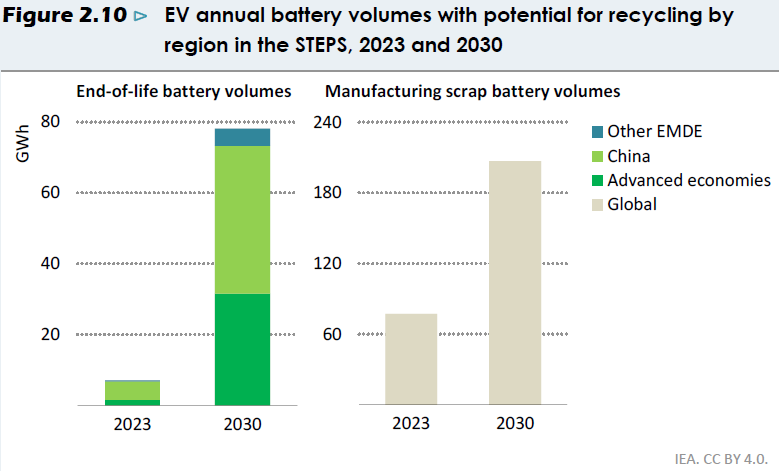

Improved understanding of the global battery supply chain and battery construction challenges has highlighted the need for a standardized method of assembling commonly used batteries worldwide. Any uniform battery assembly design must also account for disassembly and recycling of components after their initial use. Proper disassembly and recycling processes can save refurbishment time and mitigate e-waste. The appetite for battery recycling is growing based on the battery usage that will not slow down anytime soon. Figure 2.10 shows end-of-life battery volumes and manufacturing scrap battery volumes growing in the next seven years.

The Battery Supply Chain

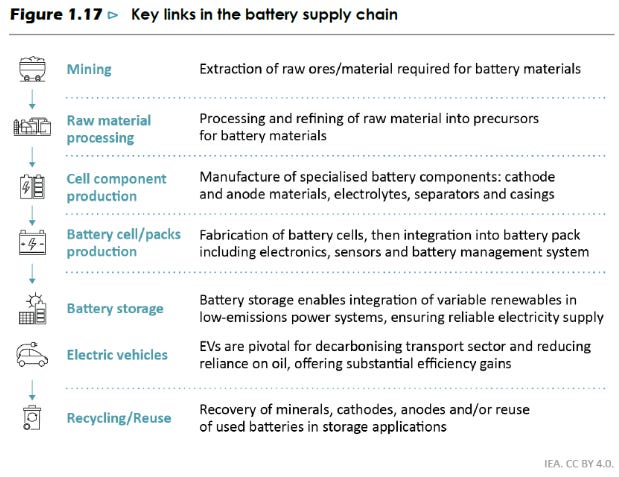

China is the frontrunner in every stage of the global battery supply chain. Figure 1.17 shows the key steps in the battery supply chain. The interdependent process requires key operational cohesion from mining the battery minerals to creating batteries for EVs and battery storage.

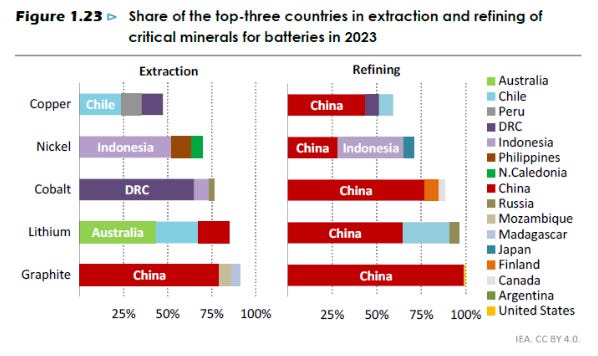

The meticulous multi-step supply chain and the critical mineral’s regional location ultimately forces the rest of the world to participate in this supply chain or consider alternative resourcing options. Figure 1.23 visualizes extraction and refining of critical minerals (step 1 and 2). The extraction steps are geographically concentrated in the eastern and central part of the globe.

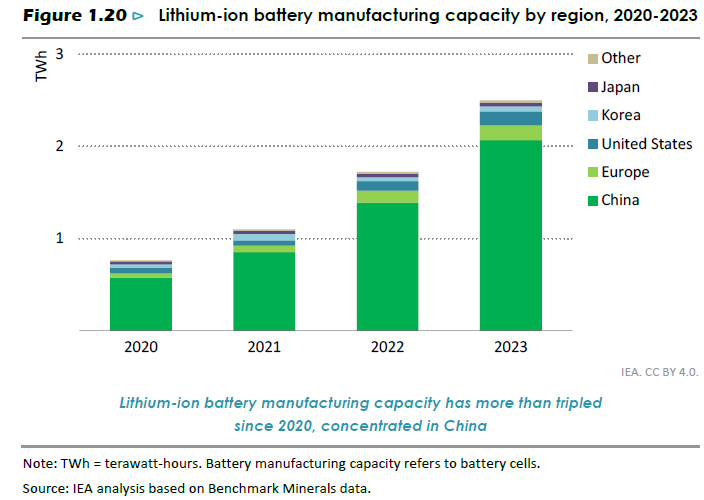

Figure 1.20 (step 3) illustrates China's dominant position in global battery manufacturing, highlighting China’s significant majority share in refining five important metals. To become independent on the other side of the world, creating partnerships with existing battery manufacturing players or rapidly developing battery manufacturers in the United States are the only options.

Leading companies in Battery Recycling

One leading company I would love to highlight is Li-Cycle. They are a lithium-ion recycling company that has a secure and routine way to retrieve important minerals from different types of used lithium-ion batteries. They break down the batteries in a controlled environment and produce a middle product called “black mass”. Li-Cycle’s black mass is then refined to a final use product of different valuable metals such as lithium, cobalt, and nickel. This refining process has a valuable material recovery rate of 95%! Li-Cycle’s Spoke and Hub model maneuvers around a battery supply chain roadblock of separating different types of metals from battery deconstruction by using their “black mass” intermediary step.

Older deconstruction methods include smelting, a high-emitting, energy-intensive process that poses significant risks to both people and the environment, and direct recovery. The smelting process occurs at very high temperatures. All batteries are burned under high heat into fuel or reductants. The minerals recovered in this process are sent to a refinery to make the minerals usable. The intensive and dangerous process leaves behind environmental pollution, major human health concerns, and a lengthy operation model to recover only a small percentage of minerals.

E-waste

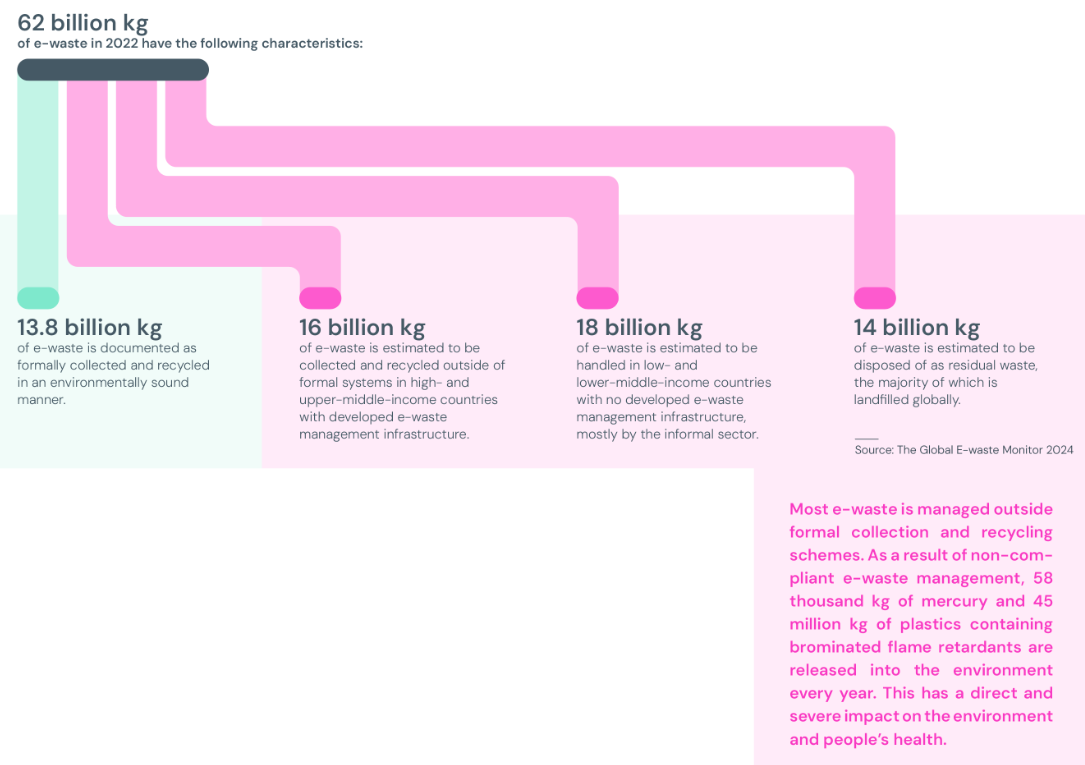

Direct recovery can be done by anyone who’s willing to salvage minerals at their own risk. Direct recovery and makeshift smelting happen around gigantic e-waste scrap yards. Unfortunately, a majority of e-waste scrap yards are in developing nations in Southeast Asia and Africa. E-waste is a growing issue driven by the overconsumption of new electronics and the misleading practice of categorizing old devices as 'used goods,' a blanket term that often leads to improper disposal rather than recycling or repurposing. This Global E-Waste Monitor article measured the increase in e-waste over the last two decades. The consumption is endless, with a record 62 million tonnes of e-waste produced in 2022 and forecasts to rise 32% to 82 million tonnes by 2030. A global battery recycling program would limit the excessive amount of dangerous materials added to the mountains of e-waste and help recover critical minerals.

A Bull, Bear, and Base Case Scenario

Bull Case Scenario

Policy

An optimal scenario involves scaling a variety of batteries to achieve the widespread adoption seen with lithium-ion batteries, while also developing a domestic recycling program to reduce reliance on the global battery supply chain. Over the past two years, significant legislation has been enacted to accelerate the growth in battery development and recycling measures.

For instance, the $370 billion Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022 stands as one of the largest renewable energy investments, offering tax credits for businesses and funding green technology research to combat climate change. Specifically for energy storage, the IRA provides a federal tax credit of up to 50% for storage projects. Similarly, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021 allocated $550 billion for clean energy infrastructure, including electric grid modernization.

The government's collaboration with private companies through targeted grants and loans to address specific challenges is fostering innovation, making this partnership method an exciting development. One notable example is the $1.2B loan for Entek to construct a factory in Indiana to produce lithium-ion battery separators, a critical component in the battery supply chain (step 3). These policy incentives and strategic investments are essential for driving cooperation between the government, private sector, and public companies.

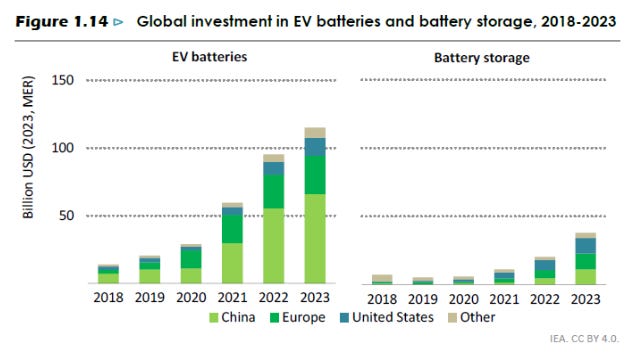

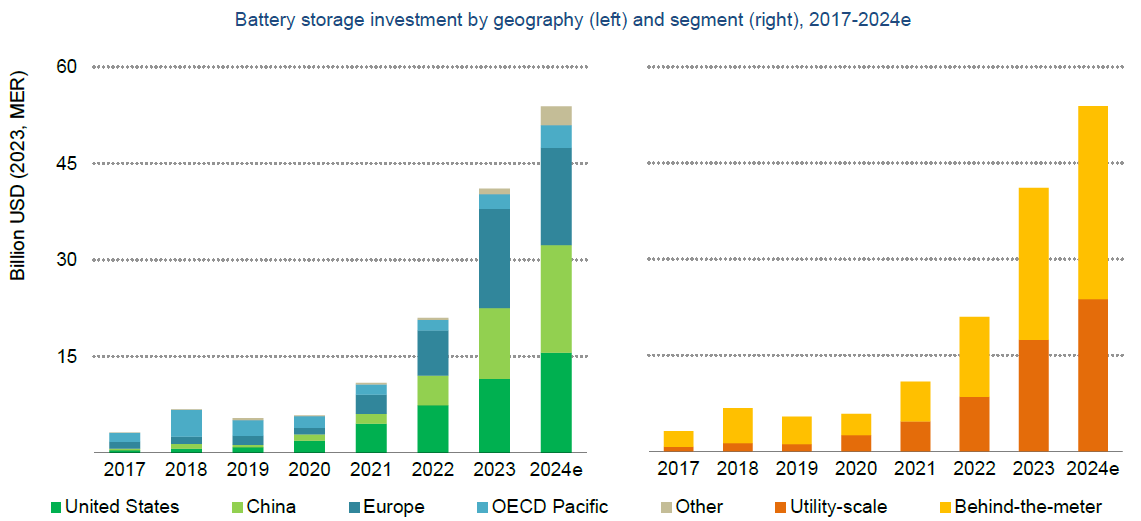

Investment

Both private and public companies are increasing investment in batteries and battery storage. Investment in EV batteries and battery storage has grown to a total of $150 billion dollars in 2023. EV batteries accounted for USD $115 billion and battery storage for USD $40 billion.

The U.S. private market plays a crucial role in achieving energy and climate goals, already contributing to 15% of global clean energy investment. VC investment in start-ups have mirrored the two charts above. Renewables, energy efficiency, energy storage and batteries, and mobility make up the bulk of the investment in both early stage and growth stage startups in the last two years.

Similar to the significant decline in EV battery costs, the IEA forecasts a similar cost reduction for battery storage, which is expected to drive growth in storage projects across developed economies. In 2023, battery storage reached more than USD $40 billion, concentrated in China, the United States and Europe. Conversely in developing economies, battery storage projects face significant obstacles including higher costs of capital and the absence of a clear regulatory framework.

Bear Case Scenario

Given the complexity of the global battery supply chain and China's significant lead, is it even possible to create and invest in a domestic battery supply chain in this part of the world?

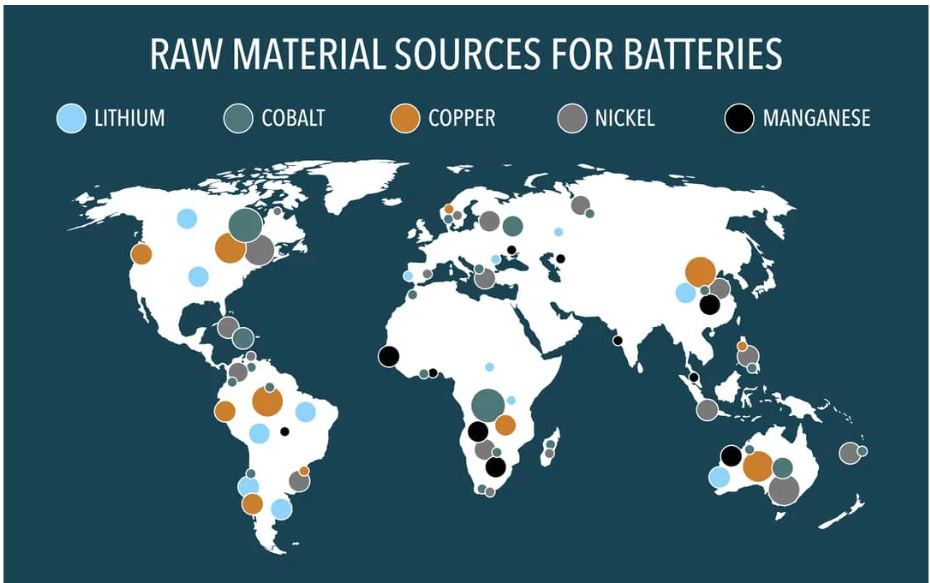

The most challenging barrier lies in the complex global network required to mine and process battery minerals, which involves multiple stages across various regions. Logistically, critical minerals are geographically concentrated in specific areas. The map below illustrates the global distribution of raw minerals, showing their location across different parts of the world.

The concentration of critical minerals around the world is unavoidable, with a geographical distribution that favors nations in the eastern hemisphere. This proximity makes it easier for eastern countries to mine and process minerals locally or ship them short distances, unlike the more costly logistics of transporting them to the United States. Recent legislation has invested millions into bringing parts of the battery supply chain stateside, but will this investment be enough? Or will the government need to spend even more to narrow the gap, only for marginal returns?

Even with policies and grants supporting the development of a closed-loop battery recycling model, can these positive measures evolve into an official U.S. recycling standard that every public company must comply with if it's material to their industry? Enlisting private companies to help develop a nationwide recycling program is a significant challenge. The European Union and the United States have taken slightly different approaches in creating the EU Battery Regulation and the US Battery Recycling and Critical Mineral Recovery Act. The EU Battery Regulation aims to regulate the whole lifecycle of batteries from sourcing the batteries in an environmentally safe way, implementing requirements for collection and recycling of batteries, a battery passport to track battery lifespan, and set targets for recycling valuable metals. The US Battery Recycling and Critical Mineral Recovery Act specific focus is on recycling batteries and the recovery of critical minerals in order to bolster the domestic supply chain. Although bolstering the domestic supply chain and making sure critical metals are not wasted is vital, a single global regulation should resemble an enhanced version of the EU Battery Regulation because the regulation comprehensively addresses the entire battery life cycle.

Base Case Scenario

The probable outcome, considering the positives in the bull case scenario and the challenges of interdependent components in the global battery supply chain, will likely result in a middle ground for battery research and development, recycling, and localized supply chains. Investment to reach net-zero goals must grow, especially as demand for EVs and energy storage projects rises and battery production costs drop. The transportation sector proves to be a consistent market for battery demand that won't go away. Government grants are spurring innovation and collaborating with private companies to create domestic supply chains. However, the sheer scale and current solidification of the global battery supply chain, coupled with the lack of unified global regulations, will make efforts to design a reliable domestic battery supply chain more cumbersome. As a result, I predict delays in mass battery assembly and disassembly for secondary use due to the absence of regulations. However, I hope to be pleasantly surprised and see outcomes closer to my bull case scenario. Let’s see what happens.

Want to chat more about my piece or the energy transition in general?

Connect with me on LinkedIn and put some time here!

P.S. This industry is rapidly changing year over year (and even month by month). Open to considerate conversations and fact or source-checking. I see every opportunity as a chance to grow and learn.