Welcome to Climate Drift - your go-to source for unraveling climate solutions and discovering your part in the net zero revolution.

If you haven’t subscribed, join here:

Hey there 👋,

It's Skander here.

Ever wondered why 9 out of 10 startups don't make it? Get ready to explore the infamous "Death Valley Curve," a perilous period for startups, and discover how climate entrepreneurs need to overcome not 1 but 4 distinct valleys of death.

Are you ready to brave the climate tech desert and shed light on the path to Net Zero? We'll have some real-life climate tech examples to guide us, and maybe even a few glimmers of hope to keep us going.

Time to dive in. 🌊

🚀 If you want to make a difference and bring your talent into climate:

Apply to our next cohort and join the Climate Drift Accelerator.

Interviews and admissions are happening right now.

Surviving the Four Valleys of Death

Intro

Around nine in every ten start-ups don't make it. But when it comes to climate tech, which holds the keys to achieving Net Zero, failure is a luxury we can't afford. It's time to map out the valleys claiming so many startups and learn how to navigate them.

In the realm of conventional software startups, there's a perilous period known as the "Death Valley Curve." It's the time when the business is operational but revenue is still a distant dream. This metaphorical desert has claimed many startups, succumbing when funding and product-market fit don't arrive in time.

Death Valley Curve: A Graveyard of Startups

This valley charts a dramatic J curve. In simple terms, sink or swim. At its lowest ebb, the startup is floundering, but once the elusive product-market fit is found, capital and revenue flow like spice in the desert.

For Climate startups

In the world of climate tech, the stakes are different and often higher. Unlike the rather straightforward paths in software, the journey here is filled with hardware, scientific challenges, and real-world complexities that slow down the race to market.

In short: In the real world things take longer and are harder than software.

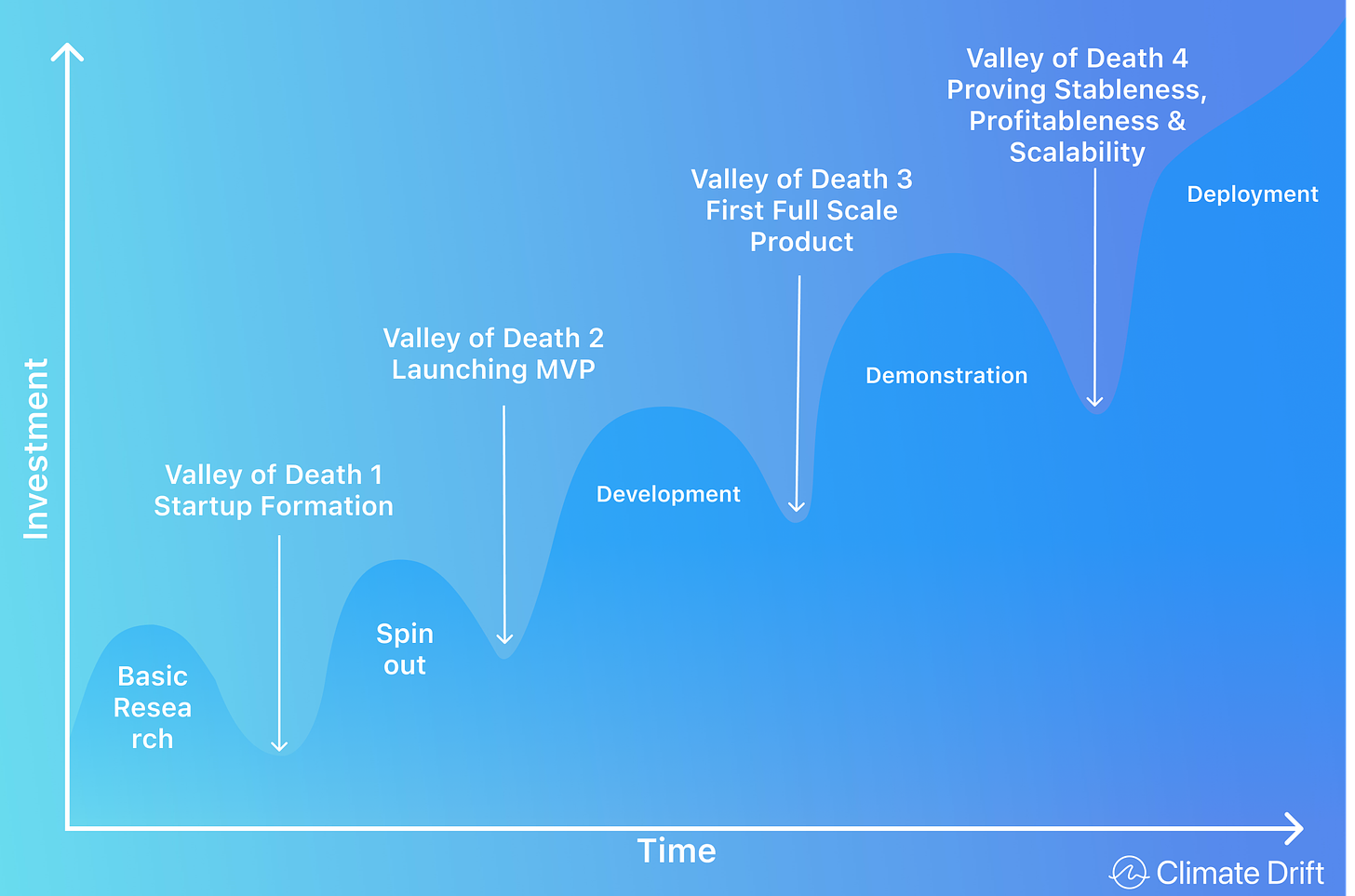

Climate tech isn't about crossing a single valley; it's about navigating a perilous journey through four distinct and daunting valleys:

Spinning out the Technology and Forming a Startup: The first valley is filled with the promise of innovation but plagued by the struggles of taking lab-born technologies to the real world. It's here where the Technological Readiness Level Framework comes in.

Finding first Product-Market Fit and Launching a Minimum-Viable Product into a Complex Market: The second valley is a labyrinth where the path to the market isn't straightforward. Climate tech must mesh with existing infrastructures, policies, and expectations.

Demonstrating the First Full-Scale Commercial Product or Facility: The third valley is where the rubber meets the road. Here, a startup must prove that its product or solution isn't just viable but works on a bigger scale. It's not about promise; it's about performance.

Proving that Products Are Stable, Profitable, and Scalable: The final valley is about long-term success. It's not enough to break through or even to succeed in a limited scope. They must be sustainable, profitable, and capable of growing.

Let’s dive into these four Valley of Death, as always spiced up with some climate tech examples.

The First Valley of Death:

Spinning out the Technology and Forming a Startup

First things first: let's talk about that infamous first hurdle, the ordeal of spinning out the tech and getting the startup off the ground. For all the talk of a climate tech revolution, there's a serious lack of these disruptive ideas making it out of the university labs and into the startup scene. And you can't exactly blame the researchers. The bar is set crazy high for them.

Investors, keen to back a winning horse, are more inclined to pour their dollars into mature technologies than into these unproven early-stage ideas. After all, it's like comparing a well-oiled machine to a prototype that’s just come off the drawing board.

With minimal funding, startups find themselves bereft of experienced executives to lead the charge. Instead, they have to make do with fresh-faced Ph.D.s and postdocs, who are usually elbow-deep in equations rather than executive decisions.

Fortunately, there are a few glimmers of hope on the horizon. Take the MIT Engine, for instance, and other such idea-spinning systems. These platforms are stepping in to fill the void, throwing out life-rafts to these would-be entrepreneurs in their journey across the first valley of death. But it's just the start, and there's a long road (or should I say, valley?) ahead.

Second Valley of Death:

Finding Product-Market Fit by Launching a Minimum-Viable Product

Alright, so you've made it through the first valley. You've spun out your tech and established a startup. Kudos! But don't pop the champagne just yet. The second valley of death is coming up fast and furious: finding the perfect product-market fit and launching your MVP into a market that's more convoluted than a maze designed by Escher.

The struggle is real for climate-tech startups. They're trying to launch their first MVP, but perfecting that initial product-market fit is like attempting to thread a moving needle. When it comes to direct-to-consumer or software startups, there's a well-thumbed playbook to follow. You know the drill: lean startup methodology, rapid prototyping, agile development, and voilà - you've got yourself a market-ready product.

But climate-tech startups? Yeah, not so much. They're not flying solo in a void. They're more like a single piece of a gigantic, interlocked puzzle, needing to slide smoothly into existing value chains and markets. So, they're not just creating a product. They're tasked with deciphering the intricacies of regulatory standards, pandering to incumbent corporations, fitting into established manufacturing processes, and threading themselves into pre-existing supply chains.

Imagine having to create a product that's not just on par, but surpasses the existing standards and specs of this interlinked system. It's like being thrown into the deep end, fresh out of the lab, often without the industry experience or contacts to help keep you afloat.

Third Valley of Death:

Demonstrating the First Full-Scale Commercial Product or Facility

Navigating the next valley can feel like navigating a minefield. Often tagged as "death by pilots," this stage is marred by the structural hurdles of working within incumbents’ lengthy and risk-averse development cycles.

Whether it's a breakthrough in carbon capture technology, green hydrogen production, or waste reduction software, climate tech pioneers need to either coax the industry giants to step aside or join them in their journey. However, these established entities are often resistant to disruptive alterations: they tend not to anticipate them, question their revenue potential, grapple with their execution, and feel threatened by their impact on existing operations.

What's the consequence? Some start-ups, spotting no alternative route, strive to sidestep the incumbents by erecting their self-reliant, vertically-integrated realm (contemplate the approach of a company like First Solar). First Solar, a leading solar PV manufacturer, didn't just pioneer thin-film PV modules; they also engaged in all-encompassing operations from manufacturing to installation and recycling of their solar products, building a holistic ecosystem. But such a comprehensive pursuit is out of reach for most climate-tech start-ups, lacking the funding or expansive reach. These startups instead find themselves in a complex dance of negotiation with entrenched industries and other stakeholders.

Fourth Valley of Death:

Proving that Products Are Stable, Profitable, and Scalable

The journey through the valleys of climate tech innovation culminates in the fourth and perhaps the most daunting valley. This is where products must prove themselves in three critical dimensions: stability, profitability, and scalability.

Stable: Ensuring a product is stable is about providing consistent, reliable performance. Grid-scale batteries, for example, must be dependable in storing and releasing energy, and their integration with existing power grids should be seamless. They must adapt to fluctuating demands and adhere to regulatory standards, a complex task in an ever-changing energy landscape.

Profitable: The second challenge is achieving profitability, which entails understanding market dynamics, regulations, and pricing. Electric vehicle charging infrastructure could serve as an example here. To be profitable, these systems must accommodate various vehicle types and charging speeds, align with regulatory policies, and be priced competitively. Striking the right balance can make them profitable and encourage wider adoption of electric vehicles.

Scalable: Finally, scalability is about adapting a model or product to a larger scale without losing efficiency. A case in point is geothermal energy. To become scalable, geothermal projects must navigate geological complexities, find suitable locations, build efficient power plants, and connect to existing energy grids. Scaling geothermal energy requires intense planning, investment, and innovation to be feasible on a broader scale.

Crossing this fourth valley involves transforming promising climate technologies into stable, profitable, and scalable solutions. It's a complex and nuanced phase, requiring a blend of technological acumen, strategic agility, and market insight and cash on hand. The examples of grid-scale batteries, electric vehicle charging infrastructure, and geothermal energy underscore the multifaceted nature of this challenge.

But remember, in our quest for Net Zero, it's go big or go home - every solution needs to scale up and make some serious waves!

Thanks for sticking with us through the second installment of our 4-part deep dive. Up next, we're tackling the Market Share S-Curve. Forget the textbook definitions; in the Climate Tech world, this S-Curve isn’t just about numbers and graphs. It's about capturing the real-life zigzagging journey of technological adoption. Think early adopters, mass markets, and everything in between.

But don't be fooled by its simplicity; this curve is like a roller coaster ride, only less about thrills and more about understanding the essential dynamics of market evolution.

See you next time,

Skander

PS: Know somebody who would love to learn more about the valleys of death? Share this post with them.